Americanized: Rebel Without a Green Card by Sara Saedi is our Underlined Book of the Month pick!

This memoir has it all—humor, heart, and those oh-so on point lines that we underline and remember forever. We picked a few of our favorite quotes, which are sure to get you thinking, feeling, and adding this to the top of your TBR pile (and we’re throwing in a sneak peek so you can start reading today!)

Ready to start reading? Here’s a sneak peek of Americanized by Sara Saedi!

Introduction

Puberty is the equivalent of guerrilla warfare on your body. Society commonly refers to it as the awkward phase, but I’ve always preferred to call it the “everything totally sucks and I hate my life” phase. I, for one, don’t miss 1993. That was the year I naively thought my biggest problems were my underdeveloped breasts, the cystic acne that had built a small colony on my chin, and the sad fact that my prettier best friend and I had set our sights on the same guy. Would our friendship fall apart over a boy? Would I ever outgrow my training bra? Would my skin ever clear up? These were the dilemmas that kept me up at night. I thought there was no way my life could get worse.

But I was wrong.

What seemed like a mundane afternoon would go down in history as the day my world crumbled. My older sister, Samira, and I were hanging out in the kitchen, probably dining on our favorite light Entenmann’s coffee cake. I worked on my homework while Samira pored over job applications for a dozen or so retail stores at the posh Valley Fair mall in our hometown of San Jose, California. Our parents owned a small luggage business about a forty-minute drive away, and they were never home before dinnertime. And so the task of watching over my younger brother and me fell to my sister. But I was cool with that, because in my opinion, an older sibling had two primary reasons for living:

- Expose their younger siblings to the harsh realities of the world.

- Protect their younger siblings from the harsh realities of the world.

This story covers number 1. I don’t think my sister derived any pleasure from blowing my carefully crafted reality to pieces, but maybe she couldn’t handle being alone in her teen angst. My parents told her things they thought I was still too young to know, but I was nearly thirteen and it was time I learned the truth about our family. It was time I learned the truth about myself. And it was her duty in life to be the one to break it to me.

“No one will ever hire me,” my sister said, frustrated. “I’m never gonna get to make my own money.”

I wanted to tell her that as long as she could keep her somewhat problematic attitude in check during a job interview, I didn’t think she’d have a problem finding long-term employment.

“Sure you will,” I reassured her. “You already have sales experience working at the luggage store.”

“That’s different. I worked for Mom and Dad. All the stores at the mall want a Social Security number,” she vented.

At the time, I’d never heard of the term “Social Security number.”

“So?” I asked.

“So I don’t have one,” she responded. “And neither do you.”

Her response clarified nothing. Who cared if we didn’t have Social Security numbers? We had a phone number and an address. What else did a person need to apply for a job?

“You’re not getting it,” Samira continued. “The government doesn’t know we exist. We could get deported at any time.”

I heard the words as they came out of her mouth, but my young mind didn’t know how to process them. Deported? I had trouble reconciling the definition of the word with the fact that we’d been living in the Bay Area for ten years.

“Like, they could send us back to Iran?”

“Yes,” she said.

“Even Kia?” I asked. My brother was almost five years old then. He was objectively adorable. Why would anyone ever want to deport him?

“No,” she explained. “He was born here. He’s a citizen.”

That entitled brat! I glared at him, sitting in the next room eating Oreos and watching Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, blissfully unaware that his sisters might get shipped back to the Islamic Republic. My anxiety tripled when Samira explained that not having a green card or a Social Security number also meant we were breaking the law simply by living in the United States. “We’re illegal aliens.” This was before “undocumented immigrant” became the more commonly used (and politically correct) term. The words “illegal aliens” echoed through my head. Suddenly hormonal acne and microscopic boobs paled in comparison to the revelation that I was a criminal. And, apparently, an alien? How would I explain this to my law- abiding, human friends? They’d probably want nothing to do with me once they learned I technically wasn’t allowed to be living in the country. If this got out, I could lose everything. But when my parents came home that night, they assured me that no one was going to deport us. We weren’t criminals or extraterrestrials. We were trying to get green cards. It would all work out and no one would have to go back to Iran. “So we won’t have to leave America?” I asked. “Na, Baba!” my dad said to me. This sort of translates to “No way, Jose!” But I wasn’t exactly convinced. That night, when I went to bed, I was no longer worried about eighth- grade love triangles or whether it was possible that Clearasil was just an elaborate scam that gave insecure teens false hope. I was worried what my life would look like if I had to say good-bye to my friends and move back to Iran. My Farsi was rusty at best. Being forced to wear a head scarf would only accentuate my bad skin. I’d already been living in the United States for a decade. How would I ever adjust? My sister’s warning stayed with me like a refrain through the rest of my teen years:

We. Could. Get. Deported. At. Any. Time.

There was only one appropriate reaction:

Holy. Shit.

“Yes, my sin—my greater sin . . . and even my greatest sin is that I nationalized Iran’s oil industry and discarded the system of political and economic exploitation by the world’s greatest empire. This at the cost to myself, my family; and at the risk of losing my life, my honor, and my property. With God’s blessing and the will of the people, I fought this savage and dreadful system of international espionage and colonialism.”

—Mohammad Mossadegh, former prime minister of Iran, defending himself against charges of treason, December 19, 1953

Chapter One

A Brief (but Juicy) History of My Birthplace (and My Birth)

I swear on my autographed copy of Ethan Hawke’s debut novel that this chapter will not be dull, so please don’t skim or skip over it. If you won’t take my word for it and have no vested interest in broadening your worldview, here’s the most important takeaway: Iran is not pronounced i-RAN; it’s pronounced e-RON. Spread the word. Tell all your friends. Tweet it. Shout it from the rooftops. Correct people. It’ll make you sound smart and cultured. On behalf of my fellow Iranians (e-RON-ians), we thank you.

Now for those juicy historical details you were promised! Real talk: Iran has dealt with its fair share of strife and political unrest. And while I’m not one to point fingers or lay blame . . . the United States and Britain were totally at fault. Okay, that’s not entirely accurate. The West might not be directly accountable for all of Iran’s drama, but they definitely stirred the pot back in the early 1950s. During that time, Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh ruled Iran. Personally, I consider the man a hero. He was a democratically elected leader, and a progressive. But his main claim to fame was that he nationalized Iran’s oil industry. Prior to Mossadegh, the country’s most valuable resource was under British control. But why let the Brits instead of Iranians profit off of Iran’s most lucrative industry? That’s the equivalent of Kanye West pocketing all the profits from 1989 (the Taylor Swift album, not the year in history). Thus, Iran told the British oil companies to hit the road, and the Brits were predictably pissed. Mossadegh to Britain: “Bye, Felicia.” So Britain decided to call in a favor from their bestie: the United States. If texting had existed at that time, then Winston Churchill would have sent President Eisenhower a bunch of crying- face emojis. According to Churchill, they needed to get rid of Mossadegh. The United States was initially reluctant to get involved, but Britain pointed out that Iran’s beloved prime minister had newly gained the support of the Tudeh Party (an Iranian communist party) and the country would eventually go red. (Oh, hell no, it wouldn’t. Our man Mossadegh wasn’t even a fan of socialism. Not to mention, the Tudeh Party frequently turned against him.) So Eisenhower said, “We’re in!” And that’s when the CIA and Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service decided to buddy up and formulate a secret coup to overthrow Mossadegh. They called it Operation Ajax. Possibly named for the mythological Greek hero or the cleaning product. Your guess is as good as mine. It was decided that Iran’s ruling monarch at the time, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (yes, “Mohammad” is like the “Mike” of Iran), would take over for Mossadegh. Initially, the shah said, “You people are nuts! Everyone loves Mossadegh. You’re asking me to commit political suicide.” But then the United States threatened to dismiss the shah as well, and he was like: “How soon do we get this overthrow party started?”

Long story short, the coup was a success. Mossadegh was jailed for three years and then placed under house arrest, till his death in 1967. Kind of ironic that today the United States would really love more democratic countries in the Middle East, and Iran was one, until the CIA got involved. J’accuse! The short-term wins for the United States and United Kingdom included regaining limited access to Iran’s oil by having a stake in a holding company called Iranian Oil Participants, or IOP. After the overthrow of Mossadegh, public opinion in Iran was so against the Brits taking total control of the country’s oil supply again that IOP was the United Kingdom’s next best option.

Meanwhile, post-coup, the shah and his family were living it up on diamond-studded thrones until everything went off the rails again in 1978. This time, the political unrest wasn’t orchestrated by foreign powers. It was the people of Iran who were fed up with the monarchy, and they had good reason. For starters, the Pahlavi family was ridiculously rich, and shamelessly extravagant with their money. Iranians respected properly gained wealth, but they objected to the shah’s fortune because much of it was stolen from the people. Which is why, beyond the walls of the palace, the country’s economy was in the crapper. Families struggled to put food on the table, while the royal family spent hundreds of millions of dollars on parties to celebrate the monarchy. Not to mention that the shah had a secret police force called SAVAK, which had a reputation for torturing and executing anyone who opposed the monarchy. (Side note: America and Israel helped establish SAVAK. In fact, the CIA helped train the officers, which means they played a significant role in the torture and murder of thousands of shah detractors.) But at this point, even the United States was over the shah because . . . wait for it . . . he increased the price of oil. The overwhelming dislike for the Pahlavi dynasty gave birth to the Iranian Revolution, and by then my parents were also fed up with the regime’s inhumane tactics. My baba, Ali, joined the protests, and eventually the shah was exiled. Mostly everyone in Iran: “SWEET!” But with every revolution comes the risk that the new regime might suck worse than the old one, and some felt that happened when the Ayatollah Khomeini (the guy with the long beard and turban— “ imam” accessories that many now associate with stereotypes like terrorism) came into power. Keep in mind that the Tehran of my parents’ generation (during the shah’s reign) was a burgeoning metropolis with European sensibilities. My maman walked the streets of her *Maman means “mom” in Farsi. During his bachelor days, my dad regularly had girlfriends he could take out in public. The consumption of alcohol was legal, and no one had to worry about the religious police arresting them for throwing a coed party. Tehran (the country’s capital) was a vacation hot spot, and a travel destination for many Westerners. Also, just so we’re clear— my parents didn’t travel around town on a camel. If you want to picture Tehran in your head, don’t conjure up images of Agrabah (the fictional city in Aladdin). Think New York City. But when Khomeini came to power, he founded the Islamic Republic of Iran and introduced Islamic law* to the country. Suddenly there were strict dress codes for women that required them to cover up their hair, men and women (unless they were married) were mostly segregated, Western music and movies were banned, and alcohol became illegal. For some, Khomeini was a total buzzkill. Of course, the new laws thrilled the country’s religious citizens, but my mostly secular family wasn’t having it. My mom had great hair. It would have been a cardinal sin to cover up those luscious chestnut locks. That said, while the country was deprived of my mom’s shampoo- commercial- quality tresses, there were also benefits to the Islamic Revolution. For instance, the Islamic law (also referred to as Sharia) is a set of moral laws that come from the Qur’an instead of legislation by the people. Some aspects of Islamic law are observed in Iran’s legal system, but today the country mostly operates under civil law, ratified by the parliament.

Meanwhile, the shah and his family, now in exile, were desperately looking for a country to take them in. President Carter reluctantly allowed them into the United States so the shah could receive surgery for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but then all hell broke loose in Tehran. Iranians wanted the shah returned to the country so he could be tried for war crimes. When the United States refused to send him back, a bunch of Iranian students stormed the US embassy and took fifty-two Americans hostage (see: the Academy Award–winning movie Argo). As if a hostage crisis and an Iranian revolution weren’t complicated enough, by 1980 the country also found itself at war with Iraq. The conflict was mostly geopolitical, with a long-standing border dispute between both nations. With the support of the United States (ahem), Iraq invaded Iran. At this point, the United States was politically motivated to back Iraq in the war. After Iran’s revolution, the new regime was pushing hostile propaganda against the West. Iran was also gaining allies in the Middle East, and the US government worried the country would become the sole power in the region, thus wielding far too much influence. But guess what else happened in 1980?

I was born!

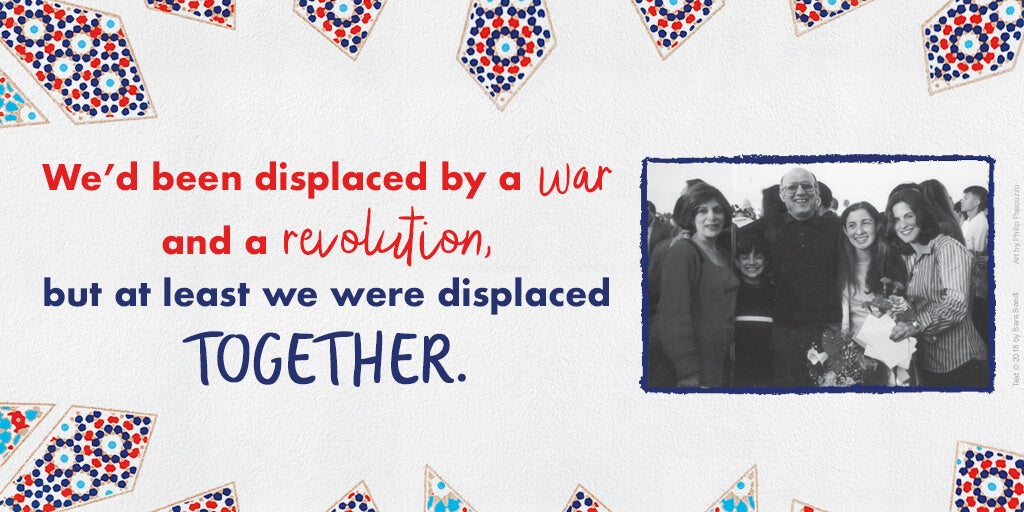

Yup, my life began during a hostage crisis, a revolution, and a war, which is why I didn’t get to enter the world on my own time. My mom’s labor had to be induced to avoid any risk of me being born during a bombing raid. Despite the tumult of the times, I was a happy, chubby baby who slept through the night and was loved by an extended family full of aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandmas. Most of my childhood photos include images of Samira and me, rolling around on intricate Persian rugs without a care in the world. We had no idea that our birthplace was in chaos and that mullahs were now running the country.

By 1982, with the hostage crisis finally over, but with no end in sight for the Iran-Iraq War or Khomeini’s rule, my parents decided to peace out of the Middle East. They feared that Iran was never going to be the same again, and didn’t want their children growing up without the freedoms they’d been afforded. There was only one problem: the borders were closed and no one was permitted to leave Iran. But my parents decided to take any means necessary to get us safely out of the country and to the United States. They chose the United States because they’d already lived there for a period of time, while my dad was in college. It also helped that my uncle had settled down in California and was willing to take us in. I suppose they had other options. They could have bided their time until the borders eventually reopened or gone through legal channels to get us green cards before we left Iran, but that would have likely taken years. With the country in upheaval, waiting would have meant putting their children’s lives at risk— a gamble they weren’t willing to take. Luckily, my dad had a friend with government ties who could secure us passports and special permission to leave the country, for a grand total of $15,000 (for my family, this was a small fortune). Only my mom (aged twenty- seven), my sister (aged five), and me (aged two) would apply to leave the country, since it was far more likely they’d grant us permission. If my dad were to have come along, the government would have assumed we were leaving our homeland for good. If he stayed behind in Iran, they figured my mom would return to her husband. The plan was that my baba would eventually find a way to follow us to America once it was safe for him to leave. In the back of their minds, I know they hoped the unrest in Iran would settle down, and we might be able to return to the country before our US visitor’s visas expired. Due to the perilous nature of our trip, we weren’t allowed to inform family members we were leaving until the eve of our flight. I don’t remember our departure, but I can only imagine what it was like for my grandmothers to hug and kiss their grandchildren farewell with no assurance that they’d ever see us again. My mom said good- bye to her husband of eight years and the love of her young life, neither of them wanting to acknowledge it could be months or years before they’d be reunited in America. Looking back on the stories I’ve heard from that time, I often wonder how my maman survived it all. She left behind her home, her entire family, and her life partner in a war-torn country to give her children better opportunities. And even though she barely spoke English, she got us all to California (by way of Paris and Zurich, where we spent weeks trying to secure a US visitor’s visa) in one piece. She’s basically the Persian Wonder Woman. Once we arrived in the States, we squatted at my dayee Mehrdad and aunt Geneva’s house in Saratoga, California. My sister and I tried to find common ground with our half- American cousins, but that took a while to pan out. It didn’t help that we’d infiltrated their space and that my sister’s favorite pastime was sending me off to bite them. I guess the rumors are true. Undocumented immigrants are violent and dangerous. The days without my dad were also seriously confusing for me as a two- year- old. My life was kind of like that children’s book Are You My Mother?, where the lost baby bird tries to find its mom. I developed a habit of pointing to male mannequins in shopping malls and asking if they were my father. But three long months after we left Iran, my dad joined us in the Bay Area. The borders had reopened, and he left the country on a “business trip” to Italy. From there, he’d obtained a visitor’s visa to the United States. But by the time my dad made it to America, I didn’t recognize him. It would take weeks before I would agree to go near him. He says my sudden shyness was one of the most heart breaking symptoms of being separated from us for so long. But at least we were back together, and our future in California was wide open. Once our visas expired, we applied for political asylum, but after two years without progress, we were told there was no record of our application. What followed was a series of messy, arduous, and complicated attempts at becoming US citizens. And a lifetime of figuring out how to fit in and be cool, without being a total traitor to my race.