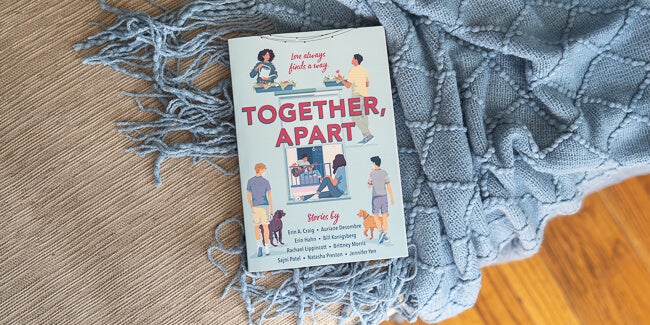

Together, Apart is a collection of original contemporary love stories set during life in lockdown by some of today’s most popular YA authors including Erin A. Craig, Auriane Desombre, Erin Hahn, Bill Konigsberg, Rachael Lippincott, Brittney Morris, Sajni Patel, Natasha Preston, and Jennifer Yen. Each unique story in this $9.99 paperback has the one thing we all want: a guaranteed happy ending. Start reading these romantic, realistic, and uplifting stories in this free excerpt now…

The Socially Distant Dog-Walking Brigade by Bill Konigsberg

The first time I met Daxton O’Brien, my dog Griffin peed on him.

I was out walking Griffin and we were in the park near my house, across from the weird alcove with the community garden and the small rock sculptures. The neighborhood has made it into an unofficial dog park, where it’s okay to let your dog off leash. It’s my favorite place in the world, because dogs. Way, way better than people. Low bar.

I always try to get Griffin to run there, but he’s not a dog that really understands play. I take him off leash and he just sits at my side, hoping for liver treats. Cut to him an hour later, staring at me with his mouth open and panting while I’m bingeing Top Chef on the couch. I’m like, You had your chance, buddy.

We were alone in the small, shaded, grassy square when a mini-parade of dogs marched by. I don’t mean like the dogs were on floats dancing, or there was a marching band and confetti; there were just six dogs.

They were all attached by leashes to people, yes, but who sees people when you can look at dogs?

In front was a gray Siberian husky, prancing like it owned the sidewalk. Then came a pair of Chihuahuas, yipping up a storm, one white and one black. Following them was a caramel-colored Pomeranian that looked like it was wearing a large-collared fur coat. Then a Weimaraner, all smooth and gray. And in the rear, an overenthusiastic doodle of some sort that was trying to sniff seven things at once. It looked a lot like my Griffin, only with black fur instead of apricot.

The Pomeranian’s person, a middle-aged lady I’d seen before, wearing red librarian glasses, waved toward me. I waved back, hoping she’d keep walking. Nothing to see here. I just wanted Griffin to do his business so I could go home and actively avoid distance-learning by playing Design Home on my phone. Griffin is sort of indifferent to other dogs, sort of like me with people.

I scanned them quickly. They were masked and appropriately distanced, and it reminded me of the one good thing about this pandemic: having a reason to steer clear of people. It can be hard to tell with masks, but the first four were clearly adults, and the one in back looked like a teenager, just about my age. One of their kids, maybe? He was skinny with blond hair and a long, thin face, and he was attempting to rodeo-wrangle the overenthusiastic doodle.

The guy in the front stopped and cupped his hands over his mask, and warily I put my hand to my ear. He lowered his mask to his chin, entirely negating the purpose of the mask in the first place. He had a bushy salt-and-pepper mustache.

“Your dog safe?” he yelled.

Safe? Like from the coronavirus? I was confused. I cupped my mask-covered mouth and yelled “What?”

“Does your dog play well with others?”

“Oh, um. Yeah, I guess. He’s . . . safe.”

I got that churning in my stomach that comes with the proximity of people. Maybe it’s my body’s reaction to danger. Fight or flight, I guess they call it. I tried to slow my breathing as the bunch of them strolled over until they were about ten feet away. They simultaneously unleashed their dogs, and Griffin went charging up to each of them to say hello. He sniffed the teen boy’s dog’s butt. He did that weird circle dance with the Pomeranian, where both dogs tried to get to the other’s behind.

It’s always weird, that moment where your dog starts sniffing another dog’s butt, and you’re standing there with their human, and suddenly you’re uncomfortably aware of both of your butts, and it’s like, Hi there, other person with a butt! Fortunately, the older guy’s husky reared back in that let’s play position, and Griffin took off across the park.

When he’s in the mood, the boy loves to be chased.

I avoided conversation by turning my head to watch. As they ran in a large circle at the perimeter of the park, Griffin looked like a big pile of apricot-colored fur blowing in the wind.

“Your dog is adorable,” the woman said.

“Um, yours too,” I said, having no idea where her Pomeranian even was at the moment.

And then it was quiet, which is the worst. Silence can be so awkward, but talking to strangers has never been in my skill set.

So the silence stayed, and it was Satan incarnate. Sometimes when I’d go to a party and wind up small-talking with someone, and they’d be droning on about how it was so hot in the summer—duh—or they hated doing homework, or something similarly banal, I would tune out, watch their facial muscles expand and contract, and I’d wonder what would happen if I just opened my mouth and started screaming.

Probably not get invited back. Which would be okay, I guess.

I glanced over at the guy my age, who was taller and better built than me. I looked away, afraid he’d see me looking. He was clearly a “Normal.” It was obvious, from his red board shorts and yellow tank top and sandals, that he was one of those people who effortlessly fit in.

Normals are tricky. They had made my life a living hell, for two years, ever since eighth grade. You had to be careful around Normals, because sometimes they shape-shifted, like with Nimo back in February. My first. We were hanging out, and they drew me in by revealing their own supposed not-normalness. And then you let your guard down, and I guess maybe they get tired of whatever they were doing with you, and now they know all your darkest, most painful stuff. And they revert back to Normal without telling you, and they never talk to you again, and take your two best friends with them.

Yes, you had to be very careful around Normals.

Griffin came running back over, a wide grin across his face, panting. He trotted up to the boy all friendly, turned ninety degrees, lifted up his leg, and he peed.

“Wha!” was all I could say.

“Whoa,” the boy finished for me, jumping back.

There was that split second before everyone started laughing where I actually thought: Run! Just run, never look back, never see those people again. But then they did laugh, and I was stuck, and all the attention was on me, and I hated my life so hard.

“Oh my god. I’m so sorry. Um.”

Everyone was laughing, including the boy, but I was dying inside. “I’m so, um. He’s never, ever, ever done that before. Never ever ever. Sorry. Sorry. Sorry.”

The boy shrugged, shaking his leg. The bottom of his red shorts and his leg seemed to take the hit. “I didn’t like these shorts anyway.”

“He owns you!” the older guy was yelling. “He peed on you, now he owns you!”

And I was like, no, please stop talking.

**

I avoided the park the next morning, for obvious reasons. Instead I headed down to Pinchot, which is pronounced Pin-Chot rather than Pin-Cho, because America. Pinchot is the best street in all of Phoenix for walking a dog. Back in the day it was part of the New Deal. They subdivided land into one-acre properties and encouraged industrial workers to farm part time. Apparently, Eleanor Roosevelt planted some trees on it. That was like the 1930s version of Beyoncé planting trees today, so it was kind of a big deal. And now, nearly a hundred years later, there’s this incredible canopy of eighty-foot-tall Aleppo pines and Washington palms on Pinchot between 26th and 27th Streets. The whole street smells like pine and fresh-cut grass.

We lived a block north, where things smelled decidedly less lovely and trees were sparse and mostly small palms. Which was why I always walked on Pinchot.

And as if the world were punking me, there they were, the same dog-walking brigade, or at least three of them, heading toward me. The woman and the man were up front and about five feet apart, and when I craned my head, I saw Griffin’s pee victim and his black doodle.

I thought about running, and this time I almost did, but then the woman waved to me again, and I sighed and realized running away would make it worse. So I kept walking, like a man toward his executioners. And while I walked, I thought about funny things I could say about the fact that yesterday Griffin had used the boy like a fence post. I came up with, I’ve stopped allowing Griffin to drink water, so you should be safe.

But when I approached them and opened my mouth, it blurted out as “Drinking water, I’ve stopped . . .” which didn’t make any sense at all.

“Hydration is important,” the woman with the librarian glasses said, nodding, as if what I’d said was somehow a normal greeting to near strangers. I thought about fixing it, but the moment was gone, so instead I just stood there and held Griffin’s leash tightly, lest he do it again. Maybe the kid was some sort of pee magnet? Who was to say?

Then Griffin did one of his Griffin things. Out of nowhere he barked, turned his head both ways, and, as if he were suddenly sure he was being stalked by a zombie, he jumped a full one-eighty, his head leading the way. And then he jumped back, and just as quickly, he returned to normal, as if whatever had just possessed him had flown away. It used to scare me when Griffin acted nuts. Now I just understood it was Griffin being Griffin.

“What the heck?” the older guy said.

“Yeah,” I mumbled, and a thing came to me as a coherent sentence, which was unusual but welcome in this case. “Griffin is basically that kid in school who sits in the back, eating chalk.”

The boy laughed and when he did so, his eyes lit up. I couldn’t see his mouth, but I imagined him with a smile where his lips pull up so high you can see his glistening gums.

This led to some laughter and the other people saying various things, none of which I heard because I was playing back in my head the moment where I successfully said something funny, and in that way, maybe Normal, almost. And who was to say what Normal really was? And then I came to, and they were all looking at me, and I realized: me. I was to say. And as previously noted, saying is not my strongest skill. Especially in front of a (potentially) good-looking boy (stupid masks). I am especially tongue-tied in the presence of (hypothetical) long-faced beauty.

So I opened my mouth, and my brain was suddenly extraordinarily empty, as if my one joke had cored me out, and the stupidest thing was that I knew as soon as I walked away, all the good things to say would come, because of course, the English language consists of many, many words, and they can be arranged in all sorts of order to make meaning. But there I was, standing like a statue, with my mouth open like an idiot, and it wasn’t getting better, the longer I stayed that way.

So I said, “Bye.”

And they each said, “Bye.”

And I walked on, knowing for the entire month of May, and for however long this pandemic thing was going on, my only goal would be to never see those people again.

**

From that point on, I stayed on the west side of 26th Street, which was decidedly less beautiful, less canopied with huge trees, and therefore less shady, which definitely mattered in Phoenix between May and September, when the flaming sun was only six or seven feet above the city at all times. Which was why I had to wake up at five-something every day to walk. Because walking dogs once the sidewalk had started to sizzle was evil and abusive, and I’d never ever do that to poor Griffin.

And maybe it was three days later, as I turned the corner from 25th Place onto Pinchot, that I saw, again, coming toward me like an unstoppable force, the masked brigade and their canines. And I thought, God, why are you doing this to me? Isn’t COVID-19 enough?

But it wasn’t, and as I walked toward them, Griffin pulling me forward the whole time, I had nothing. Nothing in my brain to say. So as I approached, I pasted on a smile they couldn’t see beneath my mask, and I said, “Hi!” and kept walking, and they all said “Hi” back. Followed by the most surprising three words of the entire pandemic thus far.

The boy turned to me as I passed, motioned my way with his hand, and said, “Walk with us.”

I turned and followed, like an obedient dog, all the while my heart pumping like I had just been threatened with a painful death rather than just walking with a bunch of strangers. I walked alongside the boy, behind the group of adults, my thump-thumping heart making it hard to hear and harder to breathe. The adults up ahead chatted with each other, and we two non-adults lagged behind.

He didn’t say anything for a while, which actually kind of helped, because it made me feel like maybe he didn’t think it was so weird that I wasn’t saying anything. But as the silence stretched on, I thought maybe it was getting rude, so I gulped, decided to pretend I was someone who could conversate, and pointed to the teen boy’s dog.

“Doodle?”

“Labra,” he said.

“Me too. I mean, not me, mine. Is. Griffin,” I said, and somehow I knew he knew I meant the dog. You never give out names with dog people, because who remembers people names?

“Squirrel,” he said back.

I raised an eyebrow. “You named your dog Squirrel?”

Out of the corner of my eye I could see him lob his head around. He had shoulder-length hair the color of hay and tanned skin. His face was so thin it made me think of those vises in shop class, and I imagined his face in there getting squeezed, which was not nice or charitable but sometimes my brain goes to weird places. “My dad,” he said. His voice from behind the mask was honeyed in that way that other queer kids sometimes talked, that way that made you kind of know it’s okay, you’re not going to get jumped. “He thought it would be funny at the dog park to yell ‘Squirrel’ when calling our dog, and all the other dogs would be like, ‘Where’s the squirrel?’ Dad joke.”

I grimaced and laughed despite myself. “Oh no he didn’t.”

“You know that thing where you think to yourself, like, One good thing about the pandemic is I’ll get to spend more time with my dad. And then you do and you’re like, Yeah, no.”

As we turned east on Earll, our dogs pulled toward the church with the perfectly manicured green lawn Griffin enjoys writhing around on. We let them lead, and soon we had that weird moment when two dogs simultaneously squat, while you wait there, both holding an empty poop bag and avoiding eye contact.

And the guy, whose name I still didn’t know, said, “Do dogs think we are mining them for their incredibly valuable poo?”

I was like, What?

He continued. “I mean, we house them, we feed them, we take them out, and when they poo, we collect it.”

“Huh,” I said. Wondering for the first time if maybe this kid was not so much a Normal.

“Daxton,” he said.

“I thought you said Squirrel?”

“No, my name.”

“Oh. Kaz,” I said.

“Good to meetcha, Kaz. Meet us again tomorrow?”

Against my better instincts, I said yes. And I admit that I felt the slightest jolt of joy, imagining more conversations with the cute, queer boy who said not Normal things.

One Day by Sajni Patel

Quarantine sucked. Especially when we were packed into urban apartments like a package of Oreos, and not even the interesting kind of Oreos, but the strange flavor that no one liked. There was no space, no quiet.

All day, my parents worked in the living room. All day, my little sister, Lilly, cohosted her summer school virtual classroom, that little teacher’s pet. She learned how to mute everyone in the first session and had gone dictator with power ever since.

“I decide who talks now,” she said in this weird, deranged voice, pressing a finger against the keyboard on my old laptop. She took up the entire dining table with her craft supplies. I mean, when had arts become so cutthroat? I could not with her.

Lilly was probably negotiating Clorox wipes and toilet paper on the elementary school black market in exchange for electronics. If she were the mastermind behind an entire underground network, no one would be surprised and my parents would probably reward her with the rarely seen fresh donut.

I rolled my eyes, grabbed a piece of sourdough (because baking as a family was our thing now), and went to the bedroom that I shared with Lilly. It was big enough for two twin beds, two nightstands, one dresser, and two desks. Every surface was covered with snacks. There were various bags of chips and cookie containers on the floor. Half-eaten bags of all four flavors of Teddy Grahams in empty popcorn bowls. Just looking at the soda bottles in the corner made my stomach hurt. Yet I still stuffed my face.

I plopped onto my bed, which I hadn’t made in who knows how long, and felt something hard slide beneath my hand as I eased back against the pillows.

“What the . . .” I snatched the controller headset. “So that’s where you went. Been looking for you since last week.” Now I could finally get back to playing video games with the girls and talk about . . . bread. Marly and Janice were also baking a lot these days. Marly had gotten into sewing super cute handmade masks, and Janice had added TikTok videos to her repertoire, which seemed more productive than whatever I was doing.

I was too bored to play. And I had a terrible stabby headache from all the screen time and noise. I just wanted to nap. Lilly’s voice carried through the hallway as she told someone named Matthew to raise his virtual hand if he wanted to talk or she’d mute him indefinitely. Then there was shuffling feet and movement and a closing door. Ma had walked into her room to her desk, which was directly behind my bed. Her muffled voice permeated the wall and went straight into my throbbing head. And Dad was on a lunch break by the sound of clanking pots and pans.

Ugh. I just wanted peace and quiet, no noise, no screens, no talking. There was always something happening from seven in the morning to ten at night. Meetings, classes, TV, cooking, cleaning, texting, talking, and even religious virtual gatherings.

I was losing. My. Mind. If it were possible to crawl out of my skin and escape into the clouds, I so would. Luckily there was a place I could escape to. My one refuge in this miserably confined, loud-as-crap world.

The balcony.

Ma was too worried about bioterrorism (aka some infected a-hole purposely coughing on us) to let us go on walks without her and Dad. But the balcony was safe.

Crawling out the window and onto the balcony, I sat outside on a folding chair four stories up. The balcony was small, partially filled with plants I’d desperately tried to grow.

“Just live,” I told them. But they didn’t seem very interested in cooperating in the muggy, summer heat. Poor roses wilted with sad, decrepit petals, and mint dried up into crispy strings.

I sighed and closed my eyes. The tall buildings kept the sunlight from directly searing my face and cast shade instead. A light breeze shifted through the air and caressed my skin. Thank goodness for shorts and thin shirts.

Beautiful, blissful quiet.

Brum. Brum. BRRRRRRUM.

What was that twangy, guttural pitch? Vibrations of something hit the air and pierced my precious silence. My stabby headache was getting agitated AF.

The sound got louder and louder until I pried open an eye and searched the balconies for the source of this . . . this racket. And then I found him. Across the wide alley, some dude in a gray T-shirt and blue board shorts sat on his balcony the next building over, one floor below, and two balconies over. His head bent low as he played a guitar. A mass of thick, black hair that needed a haircut fell over his face.

I gritted my teeth and hoped he would stop soon. But he didn’t. I glanced at my window, but there were a hundred more annoying sounds inside.

“Hey!” I shouted, cringing at the loudness. Stabby headache was going to kill me.

He didn’t hear. Dude was playing that thing like nothing else, like no one else was around. When in reality, several hundred people lived in these two buildings and I couldn’t possibly be the only one wanting quiet time.

Jumping to my feet, I shouted again, my voice scratching my throat. He paused and scanned the building until he found me glaring at him, my hands on my hips, and standing against the railing.

He waved.

I didn’t wave back. “Can you stop? I’m trying to get some quiet,” I yelled down to him, flinching from the pain in my head.

He shrugged and mouthed, Sorry. Then he went back to playing his guitar. It sounded even louder. The audacity! Did he think he just owned the air?

I needed something. I turned one way and then the other, looking for something to throw. I was heated. My skin prickled and a fire whooshed down the back of my neck. I couldn’t throw one of my sickly plants. My mom had bought those pots, and they might shatter onto someone below. In a moment of temperamental spontaneity, I tugged off my sneaker and chucked it at him with the aim and force of a seasoned softball pitcher.

As soon as the shoe left my fingers, I yelped. Gah! Oh, no! Why did I do that! Was this assault? Did I hurt him? Had I lost my favorite shoe?

I ducked just as my sneaker hit the brick side of his building. He carefully stood to find me with my hands on my face and my fingers slightly opening to peer through.

He pressed his lips together and frowned. He shook his head like he was about to call my mom and tell her what I’d done. My mom would ground me, for sure. Well, like ground me after quarantine was lifted because right now it didn’t matter. My entire life was one long, weird grounding session.

He bent down, swept up the shoe, and tossed it in his hand a few times as if he were debating throwing it back at me.

Ew. He picked up my sneaker without sanitizing it?

In the end, he saluted me with my own shoe and mouthed, Thanks.

Um. I kinda needed my shoe back, though. I wriggled one socked foot in horror. That wasn’t just any sneaker. It was one half to a glorious pair of white Converse made special by my friends. Ya know, the ones whom I may never ever see again in an actual school.

He returned to playing that hollow sound, to irritating me. I waved my arms wildly in the air to get his attention, but he just smirked and bobbed his head and got really into his music. I yelled at him again but ended up straining my voice and coughing.

“Beta?” Dad opened my bedroom door and walked to the window. “What are you doing? Who are you yelling at?”

“Some person who’s making too much noise,” I said weakly, my throat hurting from all the yelling.

He tilted his head, listened, and smiled. “Nice music. Sort of relaxing, no? Come inside and eat lunch. We have sourdough sandwiches.”

I groaned. If I ate one more slice of bread, I was going to turn into a loaf. I grunted at Guitar Boy and crawled inside.

Lunch was as peaceful as things could get these days, mainly because our mouths were busy chewing. During meals, we always kept the TV off and electronics were left on charging stations. Before quarantine, we talked about our feelings and our day while we ate, but we were so up in each other’s business now that there was no need to. Privacy? What’s that?

“Zoom meetings leave a buzz in my head,” Ma told Dad.

“It’s the earbuds,” he said. “Necessary and inevitable.”

She had a glazed look and mumbled, “I might need a drink tonight.”

“Can I sleep in the living room again?” Lilly asked as she munched on carrots.

“Sure, beta,” Ma said.

What a relief. Lilly sleeping in the living room beneath a makeshift tent with her stuffed animals and her friends on FaceTime gave me a room to myself. It was the best.

When we finished lunch, I cleaned the kitchen. Then I showered. All the while, plotting ways to get my shoe back. When I emerged from the bathroom, I spotted the dry-erase board against the wall. Hmmm. What if . . .

“Are you using the dry-erase board?” I asked Lilly.

“You may use,” she said.

“Thanks.” I grabbed the board, an eraser, and a black dry-erase marker and went onto the balcony.

Guitar Boy had left. I spotted my sneaker behind his chair. For now, I enjoyed the solace.

The Green Thumb War by Brittney Morris

Sebastian vs. the Pits

It’s been three weeks since I’ve been able to sit at my keyboard and play.

I didn’t really care that I needed stitches in my foot after they took out the glass, or that I shattered my wrist and needed surgery after I went flying into my own closet.

Or I wouldn’t have cared if my arm cast had stopped at my elbow.

But no, Mr. Doctor Man just had to go halfway up my humerus, leaving my arm stuck at an awkward L-shape for the rest of the summer, right before I was about to learn to play “Killing in the Name Of.”

I light the candle sitting on the sheet music stand and watch the flame flicker while the scent of citronella fills my room. That scent always chills me out. Reminds me of sitting around in the communal garden and staving off the early summer mosquitoes. My mom got me into aromatherapy for a science project I did in the fifth grade, and it just kinda . . . stuck.

I sigh and look just past the candle, at Hopscotch in his terrarium.

“You don’t care, huh?” I smile at the frog. “Long as I have one good hand so I can play with you.”

I reach in and pick him up gently, feeling his slippery little body settle into the palm of my right hand as he blinks one eye, then the other, in hello.

He doesn’t ribbit much anymore since he’s old now, but I can look at his eyes and know when he’s smiling at me.

And right now, he’s smiling.

“Yeah, man, you’re right,” I say, setting him back inside next to his water pot. “Gotta keep positive.”

As if on cue, the fluffy little mop of chaos in the family bolts through the door and jumps up on my leg, panting up at me.

“Yo, Oscar, I’m a little laid up now, you cain’t just be runnin’ up on me like that.” But I laugh and floof his snow white fur. I can’t stay mad at him.

And then I look up at the windowsill, at my third species of little ones to take care of. My plants. Specifically, my herbs. Sage, rosemary, lavender, and oregano. I’ve never taken care of plants before. But they’re quieter than dogs, they’re cleaner than frogs, and they only need three things: water, sunlight, and company.

I scoot my keyboard seat up to the planter box outside the window and look down at them all. Arthur—my therapist, and feelings organizer extraordinaire—told me that talking to them can help fill in the gaps he can’t fill virtually, especially now that I’ve gone and injured myself and can’t go out for walks as often as I’d like. It just hasn’t been the same meeting with him over video call. I can’t sit on that huge emerald couch in his living room with the peach walls and the fresh plants, the soft sound of running water in the fountain on the coffee table, or the faint scent of eucalyptus—he’s into aromatherapy, too.

But here, in my almost-empty room, where all my anxieties sit with me 24/7, where I lie awake at night catastrophizing everything while Mom is out driving for people all day? How am I supposed to relax here?

So I fold my arms on the sill and look at my little green friends. Mr. Lavender is coming in nicely, but he grows slow so he won’t be ready until the end of summer, while Mrs. Oregano is already sprouted and ready to go. I lean down and smell her—that herby, delicious smell that I’m used to sprinkling in dried form over pizza.

“But that’s a disgraceful fate for a plant as pretty as you, huh, ma’am? You deserve to be used for something greater, fresher. Not sure what that is yet, but—”

The sound of a sliding window catches me off guard, and I look up to see—for the first time in three weeks—the girl across the gap. That’s what Mom calls the space between our buildings—the gap. The girl looks about my age, with the bell-shaped curls that brush her shoulders when she turns each page of whatever book she’s reading. The one with the round face and the eyes as big and dark as wine grapes and sparkly as marbles.

“Hey,” she says, leaning on the windowsill and clasping her hands together as if she has more to say. She’s looking down at me with a piercing stare, and I can’t tell if she’s mad or nervous or something else.

“Hey,” I say back, leaning on my windowsill, too, and nodding at her planter box. “Nice plants. What kind?”

She seems to prickle at my question, but then she glances down at them.

“Just . . . some starters I picked up at the nursery,” she says with a sigh, cradling her hands around her elbows. “I came out here to say uh . . . sorry.” She pauses for a minute, and I must stare in confusion for long enough that she realizes I have no idea what she’s talking about, because she shrugs and continues. “For . . . your arm.”

“Oh.”

I don’t hold it against her. I know cats aren’t easy to control. It’s why dogs are better. All they want to do is eat and play. I can relate. Unless . . . this girl sicced her cat on me? Or, for all I know, she might’ve been trying to flirt with me. I’m historically bad at realizing when someone’s flirting vs. messing with me.

“It’s fine now,” I lie with a smile. “Had time to recover. Enough to take up planting these guys. I was just out here talking to them, by the way. You ever talk to yours?”

“Nah.” She smirks. “Mine are too young. Don’t think their ears have grown in yet.”

No idea what she’s talking about. They look like they’re bursting right out of the planter box like a miniature jungle.

“They look almost ready for harvest to me,” I say, craning my neck to get a better look at them. “What is that, basil?”

“That was a joke,” she says, a bit coldly. “Why are you so interested in my plants anyway? Thought you had your own to worry about.”

“Well, I think that joke was pretty corny,” I say, with the hollowest silence between us in reply. “You know, because . . . I thought you meant you were growing . . . ears of . . . corn . . . Never mind.”

“Anyway, I just came out here to apologize,” she says, turning to pull the window closed. “This doesn’t mean we’re friends.”

“Doesn’t it?” I ask, before she can leave, “Or . . . wait . . . ohhhh, I get it.”

This seems to pique her interest.

“What?” she asks with a frown.

“You must be intimidated by my awesome gardening skills,” I say. Playing with her is strangely entertaining. It’s like poking a bear that’s stuck in a building at least ten feet away, a bear that I’ll probably never see again after today if I keep poking her like this. All the entertainment with zero risk.

“I don’t get intimidated,” she says, a hint of a smile playing at the corner of her mouth for the first time today. “Certainly not by someone with such awful taste in pets.”

Ouch.

I mean, not really. Oscar is awesome. I don’t need nobody to tell me that. But that’s a personal attack right there. That’s my son she just dissed. I can’t sleep tonight if I don’t strike back—what, and miss an opportunity for free entertainment? Not I.

“Well, what if I don’t get intimidated by cat people who sit around reading all day?” I ask.

Her face goes flat with horror.

“So you’ve been spying on me,” she states. “I’ve never heard someone insult someone by admitting that.”

“Like some kind of creep? Nah, I just happened to notice, you know? It’s like living in a house by the beach and not expecting me to marvel at the view on a clear day.”

I realize too late what I’m saying, and I feel my face go hot with embarrassment.

Oscar runs over and nibbles at my foot as if to say the same thing I’m thinking: Great going, genius. This is why you don’t have any friends. But I take a deep breath and remember what Arthur said about fighting the pits. Oftentimes it takes a fight.

“I’ve got to go,” she says.

“Wait,” I say. There’s no way I can leave this conversation having just admitted to her that I think she’s . . . well . . . a view worth marveling at on a clear day. God, I cringe at how that sounds. Like bootleg Shakespeare. “Just going to leave without telling me your name?”

“Names are for people you plan to see again,” she says. This girl is pure ice inside. But it intrigues me, so I keep on. I’ve got nothing to lose. She already thinks I have horrible taste in pets and zero poetic talent. Besides, I’ve got all afternoon.

“Or for people you hope to see again,” I say.

Nice, I think. This time, her cheeks go pink, and I smile triumphantly. She frowns, rolls her eyes. “Billie,” she says. “Yes, I’m sure it can be a girl’s name. In fact, it’s the name of the girl you could learn from in the gardening department. You know, because she reads books.”

“Only if she promises to teach me,” I say. I’m not sure where this confidence is coming from, but I’m eating it up. My heart is pounding, but I’m having fun! Maybe this is what my extrovert friends have been talking about all this time. This “socializing” stuff.

“This girl doesn’t make promises,” she says, looking me up and down. “Especially to a nameless kid she just met.”

“Bastian,” I say, “Short for Sebastian. Spell it B-A-S-T-I-A-N, but pronounce it however, I’m used to it by now. Pronouns are he and him. Aquarius sun, Cancer moon, Sagittarius rising—”

“Bastian,” she says, cutting me off. “Cool. Still no promises.”

“Come on,” I beg. “What if I just want to learn? What if I want to learn how to cook with these because I’m tired of takeout?”

“Count yourself lucky,” she says, straightening and folding her arms. “We don’t eat it unless we cook it in this house.”

“Damn,” I say. That’s dedication. Must mean her parents are home all the time, then. “Do your parents work?”

“Course,” she scoffs, wrinkling her nose, “We all cook over here, not just my parents. Wai— Why am I still out here answering your questions?” She grabs the window to close it again.

“Because we’re both quarantined,” I say, “and bored, stuck at home, with nothing to do but kill time.”

“Some of us still have responsibilities,” she says.

“Like what, vacuuming? Takes five minutes.” I shrug. “Come on, my therapist said I should work on making new friends. You know how hard that is to do in lockdown?”

“You could start by not letting your dog bark at all hours of the night. Y’lose more friends that way.”

“Quicker than hucking cats through people’s windows?” I say with a laugh. I fold my arms, awkwardly because my arm is still stuck in an L shape.

“Hey, that’s a low blow. I apologized for Ruby’s behavior . . . and I didn’t huck her.”

“I’m kidding,” I say. “But that joke was in poor taste. Look, why don’t we just start over, huh? I’m sorry for my dog barking so loud over here, and you’re sorry for your cat jumping through my window. Fair?”

“You still suck at gardening,” she says. I’d assume it’s playful but her mouth is completely flat.

“How do you know?” I launch back. I look down at my plants, which I just planted a week ago. “They look fine! Bright green and lush and happy!”

“Just look at your planter box,” she says, motioning to it with her chin, “with your ‘light-skinned soil-havin’ ass.”

“Oh, and you can do better?” I ask.

“You said I could do better.” Oh no, the head wag is out now.

“Did I say you could do better, or did I say they look ready for harvest?” If all else fails in an argument, you can always catch them on a technicality.

“How would you know they’re ready for harvest if you don’t even cook?”

“You own a cat. Your apartment probably smells like cat. How do you know they’re ready for harvest if you can’t even smell them?”

“Ruby doesn’t smell,” she growls, but she’s wearing a trace of a smile. “Besides, you have a dog. How do you smell anything?”

“My dog doesn’t pee in the house like a cat!” I tease.

“Well, maybe if he did, you wouldn’t have to risk your life out here taking him to do his business.”

“Actually, my mom takes him for most of the day,” I say. I can’t help my voice getting a bit softer and sadder. “She . . . drives. People. For money. You know. She, uh . . . got laid off, so this is an in-between thing for her.”

There’s silence between us, and I can’t decide if Billie—so weird that I know her name now!—is processing what I’ve said or judging me for it. But then she sighs and leans back on the sill again, twiddling her thumbs nervously.

“That sounds dangerous,” she says, her voice now calm and soothing, like a healing salve. “Being out like that all day. With the virus and all.”

“Yeah,” I admit, letting my deep desire to brighten the mood a bit take over. “What about your mom? You said she’s out all day too. What’s she do?”

“She’s an EMT. So she’s out all day, especially now.”

“Oh.”

Definitely didn’t lighten the mood much. The awkward silence quickly takes over, and I worry I’ve gone and mucked this up, royally. Who would want to see a killjoy like me again? I turn my eyes down to my little plants, who despite all the things they must overhear out of me at their place at the windowsill, still don’t judge me. I tried, Mrs. Rosemary, I think. But then I hear it. Her voice again.

“Tell you what,” she says, straightening again. “Since you’re right, and I don’t have much to do up here, I’ll cut you a deal. You have twenty-four hours to prove you’re a better gardener than me by giving me something that you make with them, and I likewise. We’ll have to get creative, with quarantine and all, but if you’re really deserving of the ‘master gardener’ title, you’ll find a way. If I win, you keep your dog quiet, by any means necessary. Training, or even a muzzle if necessary.”

“Ouch,” I say, wincing in emotional pain. “Just gonna muzzle my best friend like that? Just gonna box in his greatness?”

She nods nonchalantly.

“As long as I’m boxed in across the alley.”

“And if I win?” I ask, my heart pounding, wondering what she’ll say.

She sighs.

“What are you hoping for?” she asks. “Help with homework?”

“Would you, uh . . .” I balance all my weight on one foot nervously. “Would you think less of me if I asked for your number?”

A car horn beeps just as I say the word number, and I worry she didn’t hear me right. But then I see red creep into her face, and she doesn’t seem to notice her cat walking under her arm and out onto the planter box until it’s too late. Reflexively, she grabs at the ball of fluff with claws, just as one of her back paws scoops out a shower of soil and sends it plummeting to the ground.

“Ruby!” she hollers, pulling the cat back through the window despite her incessant meowing. “You know better!”

When Billie pops back through the window again, she takes a long, deep breath.

“Deal.”

“Deal?!” I ask happily, hoping I didn’t sound thirsty. But the smile she gives me tells me she knows I’m walking the line.

“I said what I said, so now we’re even.” She smirks. “Almost. Matilda.”

Matilda?

“What?” I ask in confusion.

“Billie is short for Matilda. Now you know my real name like I know yours.”

I smile, glancing up at the sky and realizing it’s getting hazy and warm orange behind the purple clouds. Sunset will be here soon.

“Does that mean you want to see me again?”

“Don’t push it, Sebastian.” She smiles, leaning back into her apartment and shutting her window. Is it just me, or do her eyes linger on me for just a little longer than I expected before she draws the curtains?

“Yes!” I cry, turning and bolting for my door, sprinting barefoot past Oscar, who’s wagging his tail and bouncing around, freaking out, understandably. I scoop him up and let him lick my face.

“Oscar, you gotta help me, boy! We’ve got a gardening contest to win! Mom!” I holler out to the living room as I hear her keys jingle. Oscar runs to greet her, but I dart down the hall toward the bathroom. “Where is the beeswax?”

“What?” I hear her yell back as I rummage through cabinets of half-empty shampoo bottles and drawers of molds and bottles of oil.

“Where’s the beeswax?” I holler louder.

“Top cabinet!”

“Thanks!”

I’ve got something wonderful to make.

“The Socially Distant Dog-Walking Brigade” (c) 2020 by Bill Konigsberg

“One Day” (c) 2020 by Sajni Patel

“The Green Thumb War” (c) 2020 by Brittney Morris