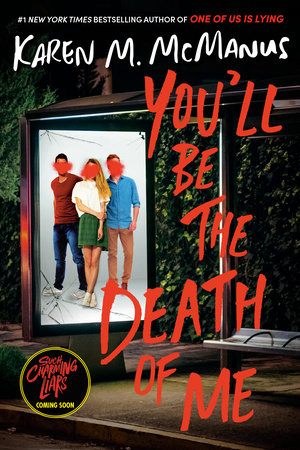

From the author of One of Us Is Lying comes a brand-new pulse-pounding thriller. It’s Ferris Bueller’s Day Off with murder when three old friends relive an epic ditch day, and it goes horribly—and fatally—wrong. Keep scrolling to read a free excerpt!

Chapter 1 | IVY

I respect a good checklist, but I’m beginning to think my mother went overboard.

“Sorry, what page?” I ask, flipping through the handout at our kitchen table while Mom watches me expectantly via Skype. The heading reads Sterling-Shepard 20th-Anniversary Trip: Instructions for Ivy and Daniel, and it’s eleven pages total. Double- sided. My mother planned the first time she and Dad ever left me and my brother alone—for four days—with the same thorough- ness and military precision she brings to everything. Between the checklist and the frequent calls over Skype and FaceTime, it’s like they never left.

“Nine,” Mom says. Her blond hair is pulled back in her signature French twist and her makeup is perfect, even though it’s barely five a.m. in San Francisco. My parents’ flight home doesn’t take off for another three and a half hours, but Mom is never anything but prepared. “Right after the lighting section.

“Ah, the lighting section.” My brother, Daniel, sighs dramatically from across the table as he overfills a bowl with Lucky Charms. Daniel, despite being sixteen, has the cereal tastes of a toddler. “I would have thought we could turn them on when we need them, and off when we don’t. I was wrong. So very, very wrong.”

“A well-lit house deters break-ins,” Mom says, like we don’t live on a street where the closest thing we’ve ever witnessed to a criminal act is kids riding bicycles without a helmet.

I keep my eyeroll to myself, though, because it’s impossible to win an argument against my mother. She teaches applied statistics at MIT, and has up-to-the-minute data for everything. It’s why I’m thumbing through her checklist for the section on CCY Award Ceremony—a list of to-dos in preparation for Mom being named Carlton Citizen of the Year, thanks to her contributions to a statewide report on opioid abuse.

“Found it,” I say, quickly scanning the page for anything I might have missed. “I picked up your dress from the dry cleaner yesterday, so that’s all set.”

“That’s what I wanted to talk to you about,” Mom says. “Our plane is supposed to land at five-thirty. Theoretically, with the ceremony starting at seven, that’s enough time to come home and change. But I just realized I never told you what to do if we’re running late and need to go straight from the airport to Mackenzie Hall.”

“Um.” I meet her penetrating gaze through my laptop screen. “Couldn’t you just, you know, text me if that happens?”

“I will if I can. But you should probably sign up for flight alerts in case the plane Wi-Fi isn’t working,” Mom says. “We couldn’t get a signal the entire way over. Anyway, if we don’t touch down before six, I’d like you to meet us there and bring the dress. I’ll need shoes and jewelry, too. Do you have a pen handy? I’ll tell you which ones.”

Daniel helps himself to more cereal, and I try to suppress my usual low-simmering resentment of my brother as I hastily scribble notes. Half my life is spent wondering why I have to work twice as hard as Daniel at everything, but in this case, I asked for it. Before my parents left, I insisted on handling every aspect of the award ceremony—mainly because I was afraid that if I didn’t, my mother would realize she’d made a mistake by asking me, not Daniel, to introduce her. My wunderkind brother, who skipped a grade and is currently outshining me in every aspect of our senior year, would have been the logical choice.

Part of me can’t help but think Mom regrets her decision. Especially after yesterday, when my one-and-only claim to school fame was brutally torpedoed.

My stomach rolls as I drop the pen and push my empty cereal bowl away. Mom, ever alert, catches the motion. “Ivy, I’m sorry. I’m keeping you from breakfast, aren’t I?”

“It’s fine. I’m not hungry.”

“You have to eat, though,” she urges. “Have some toast. Or fruit.”

The thought doesn’t appeal even a little. “I can’t.”

Mom’s forehead scrunches in concern. “You’re not getting sick, are you?”

Before I have a chance to reply, Daniel loudly fake-coughs, “Boney.” I glare daggers at him, then glance at Mom on-screen to see if she caught the reference.

Of course she did.

“Oh, honey,” she says, her expression turning sympathetic

with a touch of exasperation. “You’re not still thinking about the election, are you?”

“No,” I lie.

The election. Yesterday’s debacle. Where I, Ivy Sterling- Shepard, three-time class president, lost the senior-year election to Brian “Boney” Mahoney. Who ran as a joke. His slogan was literally “Vote for Boney and I’ll leave you alone-y.”

Okay, fine. It’s catchy. But now Boney is class president and really will do nothing, whereas I had all kinds of plans to improve student life at Carlton High. I’d been working with a local farm share on bringing organic options to the salad bar, and with one of the guidance counselors on a mediation program to resolve disputes between students. Not to mention a resource-sharing partnership with the Carlton Library so our school library could offer ebooks and audiobooks along with hard copies. I was even looking into holding a senior class blood drive for Carlton Hospital, despite the fact that I faint at the sight of needles.

But in the end, nobody cared about any of that. So today, at exactly ten a.m., Boney is going to give his presidential victory speech to the senior class. If it’s anything like our debates, it will mostly consist of long, confused pauses between fart jokes.

I’ve been trying to put on a brave face, but it hurts. Student government was my thing. The only activity I’ve ever been better at than Daniel. Well, not better, exactly, since he never bothered to run for anything, but still. It was mine.

Mom gives me a look that says Time for some tough love. It’s one of her most powerful looks, right after Don’t you dare take that tone with me. “Honey, I know how disappointed you are. But you can’t dwell, or you really will make yourself sick.”

“Who’s sick?” My father’s voice booms from someplace in their hotel room. A second later he emerges from the bathroom dressed in travel-ready casual clothes, rubbing his salt-and- pepper hair with a towel. “I hope it’s not you, Samantha. Not with a six-hour flight ahead of us.”

“I’m perfectly fine, James. I’m talking to—”

Dad approaches the desk where Mom is sitting. “Is it Daniel? Daniel, did you pick something up at the club? I heard there was a rash of food poisoning over the weekend.”

“Yeah, but I don’t eat there,” Daniel says. Dad recently got my brother a job at a country club he helped develop in the next town over, and although Daniel is only a busboy, he makes a fortune in tips. Even if he had eaten bad shellfish, he’d probably drag himself into work anyway, if only to keep adding to his col- lection of overpriced sneakers.

As usual, I’m an afterthought in the Sterling-Shepard house- hold. I half expect my father to inquire about our dachshund, Mila, before he gets to me. “Nobody’s sick,” I say as his face comes into focus over Mom’s shoulder. “I’m just . . . I was wondering if maybe I could go to school a little later today? Like, eleven or so.”

Dad’s brows shoot up in surprise. I haven’t been absent for a single hour of my entire high school career. It’s not that I never get sick. It’s just that I’ve always had to work so hard to stay on top of classes that I live in constant fear of falling behind. The only time I ever willingly missed school was way back in sixth grade, when I spontaneously slipped out of a boring field trip at the Massachusetts Horticultural Society with two boys from my class who, at the time, I didn’t know all that well.

We were seated close to an exit, and at a particularly dull point in the lecture, Cal O’Shea-Wallace started inching toward the auditorium door. Cal was the only kid in our class with two dads, and I’d always secretly wanted to be friends with him because he was funny, had a hyphenated last name like me, and wore brightly patterned shirts that I found oddly mesmerizing. He caught my eye, and then the eye of the kid next to me, Mateo Wojcik, and made a beckoning motion with one hand. Mateo and I exchanged glances, shrugged—Why not?—and followed.

I thought we’d just linger guiltily in the hallway for a minute, but the outdoor exit was right there. When Mateo pushed it open, we stepped into bright sunshine, and a literal parade that happened to be passing by to celebrate a recent Red Sox championship. We melted into the crowd instead of returning to our seats, and spent two hours wandering around Boston on our own. We even made it back to the Horticultural Society without anyone realizing we’d been gone. The whole experience—Cal called it “the Greatest Day Ever”—created a fast friendship be- tween the three of us that, at the time, seemed like it would last forever.

It lasted till eighth grade, which is almost the same in kid years.

“Why eleven o’clock?” Dad’s voice yanks me back into the present as Mom twists in her chair to look at him.

“The post-election assembly is this morning,” she says.

“Ahh,” Dad sighs, his handsome features settling into a sympathetic expression. “Ivy, what happened yesterday is a shame. But it’s no reflection of your worth or ability. That wasn’t the first time a buffoon has been handed an office he doesn’t deserve, and it won’t be the last. All you can do is hold your head high.”

“Absolutely.” Mom nods so vigorously that a strand of hair nearly escapes her French twist. But not quite. It wouldn’t dare. “Besides, I wouldn’t be surprised if Brian ends up resigning when all is said and done. He’s not really cut out for student government, is he? Once the novelty wears off, you can take his place.”

“Sure,” Dad says cheerfully, like being Boney Mahoney’s cleanup crew wouldn’t be a mortifying way to become class president. “And remember, Ivy: anticipation is often worse than reality. I’ll bet today won’t be nearly as bad as you think.” He puts a hand on the back of Mom’s chair and they smile in unison, framed like a photograph within my laptop as they wait for me to agree. They’re the perfect team: Mom cool and analytical, Dad warm and exuberant, and both of them positive that they’re always right.

The problem with my parents is that they’ve never failed at anything. Samantha Sterling and James Shepard have been a power couple ever since they met at Columbia Business School, even though my dad dropped out six months later when he decided he’d rather flip houses. He started here in his hometown of Carlton, a close-in suburb of Boston that turned trendy almost as soon as Dad acquired a couple of run-down old Victorians. Now, twenty years later, he’s one of those recession-proof real estate developers who always manages to buy low and sell high.

Bottom line: neither of them understand what it’s like to need a day off. Or even just a morning.

I can’t bring myself to keep complaining in the face of their combined optimism, though. “I know,” I say, suppressing a sigh. “I was kidding.”

“Good,” Mom says with an approving nod. “And what are you wearing tonight?”

“The dress Aunt Helen sent,” I say, feeling a flicker of enthusiasm return. My mother’s much older sister might be pushing sixty, but she has excellent taste—and lots of discretionary income, thanks to the hundreds of thousands of romance novels she sells every year. Her latest gift is from a Belgian designer I’ve never heard of before, and it’s the most fashionable thing I’ve ever owned. Tonight will be the first time I’ve worn it outside my bedroom.

“What about shoes?”

I don’t own shoes that do the dress justice, but that can’t be helped. Maybe Aunt Helen will come through on those when she sells her next book. “Black heels.”

“Perfect,” Mom says. “Now, in terms of dinner, make sure you don’t wait for us since we’re cutting it so close. You could unfreeze some of the chili, or—”

“I’m going to Olive Garden with Trevor,” Daniel interrupts. “After lacrosse practice.”

Mom frowns. “Are you sure you’ll have time for that?”

That’s my brother’s cue to change his plans, but he doesn’t take it. “Totally.”

Mom looks ready to protest, but Dad raps his knuckles on the desk before she can. “Better sign off, Samantha,” he says. “You still have to pack.”

“Right,” Mom sighs. She hates to rush when it comes to packing, so I think we’re done until she adds, “One last thing, Ivy—do you have your remarks for the ceremony all ready?”

“Yeah, of course.” I’d spent most of the weekend working on them. “I emailed them yesterday, remember?”

“Oh, I know. They’re wonderful. I just meant . . .” For the first time since we started speaking, Mom looks unsure of herself, which almost never happens. “You’re going to bring a hard copy with you, right? I know how you—I know you can get nervous in front of a crowd, sometimes.”

My stomach tightens. “It’s in my backpack.”

“Daniel!” Dad barks suddenly. “Turn the computer, Ivy. I want to talk to your brother.”

“What? Why?” Daniel asks defensively as I spin the laptop, my cheeks starting to burn with remembered humiliation. I know what’s coming.

“Listen, son.” I can’t see Dad anymore, but I can picture him trying to put on his stern face. Despite his best efforts, it’s not even a little bit intimidating. “I need you to promise that you will not, under any circumstances, mess with your sister’s notes.” “Dad, I wouldn’t— God.” Daniel slumps in his chair, rolling his eyes exaggeratedly, and it takes everything in me not to throw my cereal bowl at his head. “Can everyone please get over that? It was supposed to be a joke. I didn’t think she’d actually read the damn thing.”

“That’s not a promise,” Dad says. “This is a big night for your mother. And you know how much you upset your sister last time.”

If they keep talking about this, I really will throw up. “Dad, it’s fine,” I say tightly. “It was just a stupid prank. I’m over it.”

“You don’t sound over it,” Dad points out. Correctly.

I turn my laptop back toward me and paste on a smile. “I am, really. It’s old news.”

Based on my father’s dubious expression, he doesn’t believe me. And he shouldn’t. Compared to yesterday’s fresh humiliation, sure—what happened last spring is old news. But I am not, in any way, shape, or form, over it.

The irony is, it wasn’t even a particularly important speech. I was supposed to make closing remarks at the junior class’s spring talent show, and I knew everyone’s attention would be wandering. Still, I had the whole thing written down, like I always do, because public speaking makes me nervous and I didn’t want to forget anything.

What I didn’t realize, until I was standing onstage in front of the entire class, was that Daniel had stolen my notes and re- placed them with something else: a page from Aunt Helen’s latest erotic firefighter novel, The Fire Within. And I just—went into some sort of panicked fugue state where I actually read it. Out loud. First to confused silence as people thought I was part of the show, and then to hysterical laughter when they realized I wasn’t. A teacher finally had to rush the stage and stop me, right around the time I was describing the hero in full anatomical detail.

I still don’t understand how it happened. How my brain could have frozen while my mouth kept running. But it did, and it was mortifying. Especially since there’s no doubt in my mind that it represents the exact moment when the entire school started thinking of me as a joke.

Boney Mahoney just made it official.

Dad is still lecturing my brother, even though he can’t see him anymore. “Your aunt is a brilliant creative force, Daniel. If you have half the professional success that she does someday, you’ll be a lucky man.”

“I know,” Daniel mutters.

“Speaking of which, I noticed before we left that she sent an advance copy of You Can’t Take the Heat. I’d better not hear a word of that tonight, or I’ll—”

“Dad. Stop,” I interrupt. “Nothing is going to go wrong. Tonight will be perfect.” I force certainty into my voice as I meet my mother’s eyes, which are wide and worried—like they’re reflecting all of my recent failures. I need to get back on track, and erase that look once and for all. “It’ll be everything you deserve, Mom. I promise.”

Chapter 2 | MATEO

Here’s the thing about powerhouse people: you have no idea how much they take on until they can’t do it all anymore.

I used to think I did plenty to help around the house. More than my friends, anyway. But now that my mother is at maybe half her usual capacity, facts have to be faced: Former Mateo did jack shit. I’m trying to step up, but most of the time I don’t even think about what needs to be done until it’s too late. Like now, when I’m staring into an empty refrigerator. Thinking about how I worked five hours at the grocery store last night and never considered, even once, that maybe I should bring home some food.

“Oh baby, I’m sorry, we’re out of almost everything,” Ma calls. She’s in the living room doing her physical therapy exercises, but the whole first floor of our house is open concept, and anyway, I’m pretty sure she has eyes in the back of her head. “I haven’t made it to the store this week. Can you grab breakfast at school?”

Carlton High cafeteria food is crap, but pointing that out would be a Former Mateo move. “Yeah, no problem,” I say, shutting the refrigerator door as my stomach growls.

“Here.” I turn as my cousin Autumn, sitting at the kitchen table with a half-zipped backpack in front of her, tosses me a PowerBar. I catch it in one hand, peel back the wrapper, and bite off half.

“Bless you,” I mumble around the mouthful. “Anything for you, brousin.”

Autumn has lived with us for seven years, since her parents died in a car crash when she was eleven. Ma was a single parent by then—she and my dad had just divorced, which horrified her Puerto Rican family and totally unfazed his Polish one—and Autumn was her niece by marriage, not blood. That should’ve put my mother low on the list of people responsible for a traumatized preteen orphan, especially with all the married couples on Dad’s side. But Ma’s always been the adult who Gets Shit Done.

And unlike the rest of them, she wanted Autumn. “That girl needs us, and we need her,” she told me over my outraged protests as she painted what used to be my game room a cheerful lavender. “We have to take care of our own, right?”

I didn’t like it, at first. Autumn acted out a lot back then, which was obviously normal but still hugely uncomfortable for ten-year-old me. You never knew what would set her off—or what inanimate object she’d decide to punch. The first time Ma ever took us shopping, a clueless cashier told my cousin, “Look at that beautiful red hair! You and your brother don’t look any- thing alike.” And Autumn’s face froze.

“He’s my cousin,” Autumn said tightly, her eyes getting big and shiny. “I don’t have a brother. I don’t have anybody.” And then she drove her fist into the candy display next to the register, scaring the life out of the cashier.

I scrambled for the fallen candy while Ma put both hands on Autumn’s shoulders and pulled her away from the display. Her voice was light, like there was no meltdown happening anywhere near us. “Well, maybe now you have a brother and a cousin,” she said.

“A brousin,” I said, stuffing the candy bars back in all the wrong spots. And that made Autumn choke out a near laugh, so it stuck.

My cousin tosses me another PowerBar after I’ve polished off the first in three bites. “You working at the grocery store tonight?” she asks.

I take a huge bite before answering. “No, Garrett’s.” It’s my favorite job; a no-frills dive bar where I bus tables. “Where are you headed? Waitressing?”

“Murder van,” Autumn says. One of her jobs is working for Sorrento’s, a knife-sharpening company, which means she drives to restaurants all over greater Boston in a battered white van with a giant knife on one side. The nickname was a no-brainer. “How are you getting there?” I ask. We only have one car, so transportation is a constant juggling act in our house.

“Gabe’s picking me up. He could probably drop you off at school if you want.”

“Hard pass.” I don’t bother hiding my grimace. Autumn knows I can’t stand her boyfriend. They started going out right before they graduated last spring, and I thought it wouldn’t last a week. Or maybe that’s just what I hoped. I’ve never cared for Gabe, but I took what Autumn calls an “irrational dislike” to him the first time I heard him answer his phone by saying “Dígame.” Which he still does, all the time.

“Why do you care?” she asks whenever I complain. “It’s just a greeting. Stop looking for reasons to hate people.”

It’s a poser move, is my point. He doesn’t even speak Spanish.

Gabe and my cousin don’t fit, unless you think of it in terms of balance: Autumn cares too much about everything, and Gabe doesn’t give a crap about anything. He used to head up the party crowd at Carlton High, and now he’s taking a “gap year.” As far as I can tell, that means he acts like he’s still in high school, minus the homework. He doesn’t have a job, but somehow still managed to buy himself a new Camaro that he revs obnoxiously in our driveway every time he comes to pick up Autumn.

Now, she folds her arms and cocks her head at me. “Fine. By all means, walk a mile when you don’t have to out of sheer spite and stubbornness.”

“I will,” I grumble, finishing my second PowerBar and tossing the wrapper into the garbage. Maybe I’m just jealous of Gabe. I have a chip on my shoulder, lately, for anyone who has more than they need and doesn’t have to work for it. I have two jobs, and Autumn, who graduated Carlton High last spring, has three. And it’s still not enough. Not since the one-two punch we got hit with.

I turn as Ma enters the kitchen, walking slowly and deliberately to avoid limping. Punch #1: in June she was diagnosed with osteoarthritis, a bullshit disease that messes with your joints and isn’t supposed to happen to people her age. She does physical therapy nonstop, but she can’t walk without pain unless she takes anti-inflammatory meds.

“How are you feeling, Aunt Elena?” Autumn asks in an overly bright tone.

“Great!” Ma says, sounding even more chipper. My cousin learned from the best. I clench my jaw and look away, because I can’t fake it like they do. Every single day, it’s like getting slammed in the head with a two-by-four to see my mother, who used to run 5Ks and play softball every weekend, strain to make it from the living room to the kitchen.

It’s not like I expect life to be fair. I learned it’s not seven years ago, when a drunk driver plowed into Autumn’s parents and walked away without a scratch. Still sucks, though.

Ma makes it to the kitchen island and leans against it. “Did you remember to pick up my prescription?” she asks Autumn.

“Yup. Right here.” Autumn roots through her backpack, pulling out a white pharmacy bag that she hands to my mother. My cousin’s eyes briefly meet mine, then drop as she reaches into the backpack again. “And here’s your change.”

“Change?” Ma’s eyebrows shoot up at the thick stack of twenties in Autumn’s hand. Those pills cost a fortune. “I wasn’t expecting change. How much?”

“Four hundred and eighty dollars,” Autumn says blandly. “But how . . .” Ma looks totally lost. “Did you use my credit card?”

“No. The co-pay was only twenty bucks this time.” Ma still hasn’t made any move to take the money, so Autumn gets up and drops it onto the counter in front of her. Then she sits back down and picks up a scrunchie from the table. She starts pulling her hair into a ponytail, cool and casual. “The pharmacist said the formulary changed.”

“Changed?” Ma echoes. I stare at the floor, because I sure as hell can’t look at her.

“Yeah. He says there’s a generic version available now. But don’t worry, it’s still the same medication.”

Autumn is a good actress, but my shoulders still tense because Ma has a bullshit detector like no one I’ve ever met. It’s a measure of how rough the last few months have been that she only blinks in surprise once, then smiles gratefully.

“Well, that’s the best news I’ve had in a while.” She pulls an amber bottle from the pharmacy bag and unscrews the top, peering into it like she can’t believe it’s the same medication. It must meet her approval, because she crosses to the cabinet next to the refrigerator and pulls out a glass, filling it with water from the sink.

Autumn and I both watch her like a hawk until she actually swallows the pill. She’s been skipping doses for weeks, trying to stretch the latest bottle much further than it’s meant to go, be- cause our finances suck right now.

Which brings me to Punch #2: my mother used to own her own business, a bowling alley called Spare Me that was a Carl- ton institution. Ma, Autumn, and I all worked there, and it was fun as hell. Until six months ago, when some kid slipped on an overwaxed lane and got hurt to the point that his parents went full lawsuit. By the time the dust settled, Spare Me was bankrupt and my mother was desperate to sell. Carlton developer extraordinaire James Shepard scooped it up for nothing.

I shouldn’t be mad about that. It’s business, not personal, Ma keeps telling me. I’m glad it was James. He’ll develop a good property. And yeah, he probably will. He’s shown Ma plans for a bowling alley–slash–entertainment complex that’s a lot glitzier than Spare Me, but not stupidly out of proportion for the town, and he asked her to take on a consulting role when it’s closer to final. There might even be a cushy corporate job for her down the line. Way down.

But the thing is: James’s daughter, Ivy, and I used to be friends. And even though it’s been a while, I’d be lying if I said it didn’t suck to hear about James’s plans from him instead of her. Because I know Ivy has the inside track. She hears about this stuff way before anyone else. She could’ve given me a heads-up, but she didn’t.

I don’t know why I care. It’s not like it would’ve changed anything. And it’s not like I hang out with her anymore. But when James Shepard came to our house with his rose-gold lap- top and his blueprints, so goddamn nice and charming and respectful while he laid out how his company was going to rebuild from the ashes of my mother’s dream, all I could think was: You could’ve fucking told me, Ivy.

“Earth. To. Mateo.” Ma’s in front of me, snapping her fingers in my face. I didn’t even notice her move, so I must’ve been lost in thought for a while. Crap. That kind of zoning out worries my mother—who, sure enough, is peering at me like she’s trying to see inside my brain. Sometimes I think she’d yank it right out of my skull if she could. “You sure I can’t convince you to come to the Bronx for the day? Aunt Rose would love to see you.”

“I have school,” I remind her.

“I know,” Ma sighs. “But you’re never absent, and I feel like you could use a day off.” She turns toward Autumn. “Both of you could. You’ve been working so hard.”

She’s right. A day off would be incredible—if it didn’t in- volve at least seven hours round trip in a car with her college friend Christy. Christy offered to play chauffeur as soon as Ma said she wanted to visit Aunt Rose on her ninetieth birthday, which was great of her, since Ma can’t easily drive long distances anymore. But Christy never stops talking. Ever. And eventually, every conversation turns toward stuff she and Ma did during college that I’d rather live the rest of my life without knowing.

“Wish I could,” I lie. “But Garrett’s is short-staffed tonight.”

“Mr. Sorrento needs me, too,” Autumn says quickly. She doesn’t enjoy Christy’s monologues any more than I do. “You know how it is. Those knives won’t sharpen themselves. We’ll

call Aunt Rose and wish her a happy birthday, though.”

Before Ma can answer, a familiar roar fills my ears and sets my teeth on edge. I cross to the front door and pull it open, stepping onto the porch. Sure enough, Gabe’s red Camaro is in our driveway, engine revving while he dangles one arm out of the driver’s-side window and pretends not to notice me. He’s slouched low in his seat, but not low enough that I can’t make out his slicked-back hair and mirrored sunglasses. Would I hate Gabe less if he didn’t look like such a massive sleaze all the time? The world will never know.

I lift my hands and start a slow clap as Autumn joins me out- side, staring between me and the car with a puzzled expression. “What are you doing?” she asks.

“Giving it up for Gabe’s engine,” I say, clapping hard enough to make my palms sting. “Seems important to him that people notice it.”

Autumn shoves at my arm, disrupting the applause. “Don’t be a dick.”

“He’s the dick,” I say automatically. We could have this argument in our sleep.

“Babe, come on,” Gabe calls, lifting his arm in a beckoning motion. “You’re gonna be late for work.”

Autumn’s phone rings in her hand, and we both glance down at it. “Who’s Charlie?” I ask over another rev of the engine. “Gabe’s replacement? Please say yes.”

I expect her to roll her eyes, but instead she declines the call and shoves her phone into her backpack. “Nobody.”

The back of my neck prickles. I know that tone, and it doesn’t mean anything good. “Is he one of them?” I ask.

She shakes her head, resolute. “The less you know, the better.”

I knew it. “Are you making extra stops today?” “Probably.”

My jaw twitches. “Don’t.”

Her mouth sets in a thin line. “I have to.”

“For how much longer?” We could have this argument in our sleep, too.

“As long as I can,” Autumn says.

She hoists her backpack higher on her shoulder and meets my eyes, the question she’s been asking me for weeks written across her face. We have to take care of our own, right?

I don’t want to nod, but how the hell else am I supposed to answer?

Yeah. We do.

Chapter 3 | CAL

“It’s orange,” I tell Viola when she puts the doughnut in front of me.

“Well, duh.” Viola might be in her forties, but she can roll her eyes as aggressively as any teenager at Carlton High. “That’s the Cheeto dust.”

I poke uncertainly at one side of the doughnut. My fingertip comes back bright orange. “And this tastes good?”

“Honey, you know our motto at Crave.” She puts one hand on her hip and cocks her head, inviting me to finish the sentence.

“The weirder the better,” I say dutifully.

“That’s right.” She pats me on the shoulder before turning back toward the kitchen. “Enjoy your Cheeto-dusted Bavarian cream.”

I regard the orange lump on my plate with a mix of anticipation and fear. Crave Doughnuts is my favorite breakfast place in the greater Boston area, but I haven’t been in a while. It’s hard to find anyone willing to eat this particular style of doughnut unless they’re being ironic. My ex-girlfriend, Noemi, is gluten-free and all about clean eating, so she refused to set foot in the place no matter how much I begged. Somehow, that makes it even worse that she ultimately broke up with me at Veggie Galaxy.

“I don’t know what’s happened to you. You don’t even seem like yourself anymore,” she told me over a plate of kale and sei- tan salad last week. “It’s like aliens abducted the real Cal and left this shell behind.”

“Um, okay. Wow. That’s harsh,” I muttered, feeling a stab of hurt even though I’d seen this coming. Not this, exactly, but something. We’d barely seen each other all week, and then all of a sudden she texted We should go to Veggie Galaxy tomorrow. I had a bad feeling, and not just because I hate kale. “I’ve been a little distracted, that’s all.”

“It doesn’t feel like you’re distracted. It feels . . .” Noemi tossed her braids over one shoulder and scrunched her nose up, thinking. She looked really cute, and it hit me with a pang how much I used to like her. Still did like her, except . . . it wasn’t that simple anymore. “Like you stopped trying. You’re doing stuff because you think you’re supposed to, but it’s not real. You’re not real. I mean, look at you,” she added, gesturing toward my plate. “You’ve eaten almost an entire plate full of kale, and you haven’t complained once. You’re a pod person.”

“I didn’t realize criticizing your food choices was a prerequisite for being a good boyfriend,” I grumbled, stuffing another forkful of kale into my mouth. Then I almost gagged, because honest to God, only rabbits should eat that crap. A few minutes later, Noemi signaled for the check and insisted on paying it, and I was single once again. Sort of. Truth is, Noemi was prob- ably picking up on the fact that I’ve been interested in someone else for a while, but she didn’t have to pummel my self-esteem into the ground in retaliation.

“Take some time for yourself, Cal,” my dad said when it happened. Well, one of my dads. I have two of them—and a biological mother I see a few times a year, who’s a college friend of my dads and was their surrogate seventeen years ago—but I call both of them Dad. Which is pretty straightforward—to me—but a certain subset of my classmates finds it endlessly con- fusing. Boney Mahoney, in particular, used to ask me all the time in elementary school, “But how do they know which one you’re talking to?”

It’s easy. I’ve always used a slightly different inflection on the word with each of my fathers, something that started so naturally when I was a little kid that I don’t even remember doing it. But that’s not the kind of thing you can explain to a guy like Boney, who has all the subtle communication skills of a brick. So I told him I call them by their first names, Wes and Henry. Even though I don’t, unless I’m talking about them to someone else.

Anyway, Wes is the dad I go to with personal stuff. “There’s more to life than romantic relationships,” he said when Noemi and I broke up. He’s the dean at Carlton College, and I’m pretty sure he spends half his life worrying that I’m going to have a marriage certificate before a bachelor’s degree. “Focus on your friends for a change.”

Yeah, right. Spoken like a man who’s never met my friends, which he hasn’t, because my Carlton High circle is one of convenience. We’re all people on the fringes of school who drop one another as soon as something better comes along, then go skulking back when it ends. The last time I had real friends was middle school. Wes, who knows way more about my social life than any self-respecting seventeen-year-old should allow, claims it’s because I’ve been a serial dater since ninth grade. And I maintain that it’s the other way around. It’s the ultimate chicken-egg conversation.

At least my new girlfriend likes the same things I do: art, comics, and calorically dense breakfast food with zero nutritional value. Well, girlfriend is probably a stretch. Lara and I haven’t defined things yet. It’s complicated, but I’m all-in enough that I drove forty minutes in rush hour traffic to eat weird doughnuts with her.

I hope I did, anyway.

Ten minutes later, my doughnut’s getting stale. My phone buzzes, and Lara’s name pops up with a string of sad-face emojis. So sorry, can’t be there after all! Something came up.

I tamp down disappointment, because that’s how it is with Lara. Something comes up a lot. I knew when I got into my car that there was a fifty-fifty chance I’d end up eating alone. I pull my plate toward me and take a huge bite of my Cheeto- dusted Bavarian cream and chew thoughtfully. Sweet, salty, with a strong hint of processed cheese. It’s magnificent.

I finish the rest in three bites, wipe my hands on a napkin, and glance at the clock on the wall. The drive back to Carlton against traffic will take less than half an hour, and it’s not even eight yet. I have time for one more thing. My messenger bag is on the floor beside me, and I reach into it to pull out my laptop. The browser is already open to my old WordPress site, and with a few clicks I open the first web comic I ever made.

The Greatest Day Ever

Written and illustrated by Calvin O’Shea-Wallace

I showed all my web comics to Lara a couple of weeks ago, and she immediately claimed that this was the best of the bunch. Which was a little insulting, since I was twelve when I drew it, but she said it had a “raw energy” my newer stuff lacks. And maybe she’s right. I started it after that day in sixth grade when I skipped a class trip with Ivy Sterling-Shepard and Mateo Wojcik to wander around Boston, and there’s a certain exhilaration in every panel that mirrors how I felt about getting away with something so outrageous.

Plus, if I do say so myself, the likenesses aren’t bad. There’s Ivy with her unusual brown eyes–blond hair combination, her ever-present ponytail blowing in the wind, and an expression that’s half-worried, half-thrilled. I might’ve drawn her with big- ger boobs than she had then, or even now, but what do you expect? I was twelve.

Mateo, admittedly, I didn’t draw entirely true to life. I was supposed to be the hero of The Greatest Day Ever, and him the sidekick. That wouldn’t have worked if I’d given him that whole dark-and-brooding thing girls were already swooning over in sixth grade. So he was shorter in web comic form. And skinnier. Plus, he might’ve had a slight acne problem. But he still had the best one-liners that came out of nowhere.

“Hey! That’s you!” I jump at Viola’s voice as she reaches across my shoulder to grab my empty plate. I’ve paused on a panel that’s just me racing through Boston Common in all my red-haired, floral-shirted, twelve-year-old glory. “Who made that?”

“I did,” I say, scrolling to a new panel so my face isn’t quite so prominent. This one has Ivy and Mateo, too. “When I was twelve.”

“Well, isn’t that something.” Viola fingers the skull necklace that’s dangling halfway down her Ramones T-shirt. She was the drummer for a punk-rock band when she was my age, and I don’t think her style aesthetic has changed in thirty years. “You’ve got real talent, Cal. Who are the other two?”

“Just some friends.”

“I don’t recall ever seeing them here.” “They’ve never been.”

I say it lightly with a shrug, but the words make me feel as flat as Noemi’s You’re not real speech. Ivy and Mateo were the best friends I ever had, but I’ve barely spoken to them since eighth grade. It’s normal for people to grow apart when they reach high school, I guess, and it’s not like our friend breakup was some big, dramatic thing. We didn’t fight, or turn on one another, or say the kind of things you can’t take back.

Still, I can’t shake the feeling that it was all my fault.

“You want another doughnut?” Viola asks. “There’s a new hazelnut bacon one I think you might like.”

“No thanks. I gotta haul ass if I’m gonna make it to school on time,” I say, shutting my laptop and slipping it back into my bag. I leave money on the table—enough for three doughnuts, to make up for the fact that I don’t have time to get the actual check—and sling my bag across my shoulders. “See you later.”

“I hope so,” Viola calls as I dart between a hipster couple sporting graphic T-shirts and the same haircut. “We’ve missed your face around here.”

I don’t believe in fate, as a general principle. But it feels like more than a coincidence when I step out of my car in the Carl- ton High parking lot and almost walk straight into Ivy Sterling-Shepard.

“Hey,” she says as her brother, Daniel, grunts a semi-greeting and brushes past me. That kid’s gotten a lot taller since freshman year—some days I barely recognize him loping through school in his lacrosse gear. Nobody should be that good at so many different things. It doesn’t build character.

Ivy watches him go like she’s thinking the same thing, before turning her attention back to me. “Cal, wow. I haven’t seen you in forever.”

“I know.” I lean against the side of my car. “Weren’t you in Scotland or something?”

“Yeah, for six weeks over the summer. My mom was teaching there.”

“That must’ve been awesome.” Ivy could have used the distance, probably, after the whole junior talent show debacle. I watched from the second row of the auditorium with Noemi and her friends, who were all doubled over with laughter.

Okay, I was, too. I couldn’t help it. I felt bad later, though, wondering if Ivy had seen me. The thought makes my skin prickle with shame, so I quickly add, “This is so weird. I was just thinking about you.”

There’s never been anything except a friend vibe between Ivy and me, so I don’t worry about her taking that the wrong way, like Damn, girl, you’ve been on my mind. I’m a little surprised, though, when she says, “Really? Me too. About you, I mean.”

“You were?”

“Yeah. I was trying to remember the last time I missed a class,” she says, pressing her key fob to lock the black Audi be- side her. I recognize it from middle school, so it’s definitely her parents’ old car, but still. That’s a sweet ride for a high school senior. “It was the day we skipped the field trip.”

“That’s exactly what I was thinking about,” I say, and for a second we share a conspiratorial grin. “Hey, and congrats to your mom.”

She blinks. “What?”

“Carlton Citizen of the Year, right?” “You know about that?” Ivy asks.

“My dad was on the voting committee. Wes,” I add, which feels a little weird. Back when we were friends, Ivy always knew which dad I was referring to without me having to specify.

“Really?” Her eyes widen. “Mom was so surprised. She always says statisticians are unsung heroes. Plus there’s usually more of a local angle for the award, and with the opioid report . . .” She shrugs. “It’s not like Carlton is a hot spot or anything.”

“Don’t be so sure,” I say. “Wes says that crap has been all over campus lately. He even set up a task force to deal with it.” Ivy’s expression gets alert, because there’s nothing she likes better than a good task force, and I quickly change the subject before she can start lobbing suggestions. “Anyway, he voted for her. He and Henry will be there tonight.”

“My parents are barely going to make it,” Ivy says. “They’re in San Francisco for their anniversary, and they had to scramble to rearrange their flights to be home in time.”

Sounds like a typically overachieving Sterling-Shepard move; my dads would’ve just videotaped an acceptance speech from California. “That’s great,” I say, which feels like my cue to move on. But we both keep standing there, until it gets awkward enough that my eyes stray over her shoulder. Then I do a double take as a tall, dark-haired guy swings himself over the fence sur- rounding the parking lot. “Well, damn. The stars keep aligning today. There’s the third member of our illicit trio.”

Ivy turns as Mateo catches sight of us. He gives a chin jut in our direction, then looks ready to continue his path to class until I stick my hand in the air and wave it wildly. It’d be a dick move to ignore me, and Mateo—despite being the kind of guy who’d rather swallow knives than make small talk—isn’t a dick, so he heads our way.

“What’s up?” he asks once he reaches the bumper of Ivy’s car. She looks nervous all of a sudden, twisting the end of her ponytail around one finger. I’m starting to feel a little weird, too. Now that I’ve summoned Mateo, I don’t know what to say to him. Talking with Ivy is easy, as long as I avoid minefields like the junior talent show, or how she got crushed in the student council election yesterday by Boney Mahoney. But Mateo? All I know about him these days is that his mom’s bowling alley had to shut down. Not an ideal conversation starter.

“We were just talking about the Greatest Day Ever,” I say instead. And then I feel like a loser, because that name wasn’t cool even when we were twelve. But instead of groaning, Mateo gives me a small, tired smile. For the first time, I notice the dark shadows under his eyes. He looks like he hasn’t slept in a week.

“Those were the days,” he says.

“I’d give anything to get out of school today,” Ivy says. She’s still twirling her ponytail, eyes fixed on the back of Carlton High. I don’t have to ask her why. Boney’s acceptance speech is going to be painful for all of us, but especially her.

Mateo rubs a hand over his face. “Same.”

“Let’s do it,” I blurt out. I’m mostly kidding, until neither of them shut me down right away. And then, it hits me that there’s nothing I’d rather do. I have two classes with Noemi today, a history test I’m not ready for, no hope of seeing Lara, and nothing more exciting to look forward to than burritos for lunch. “Seriously, why not?” I say, gaining enthusiasm as I warm up to the idea. “Do you guys know how easy it is to skip now? They barely even bother to check, as long as a parent calls in before first bell. Hang on.” I pull my phone out of my pocket, scroll to Carlton High in my contacts, and tap the number that pops up. I listen to the main menu until the automated voice drones, If you’re reporting an absence . . .

Ivy licks her lips. “What are you doing?”

I press three on my keypad, then hold up a finger until I hear a beep. “Good morning. This is Henry O’Shea-Wallace, calling on behalf of my son, Calvin, at eight-fifty a.m. on Tuesday, September twenty-first,” I say in my father’s quiet, clipped voice. “Unfortunately, Calvin is running a slight fever today, so we’ll be keeping him home as a precaution. He has all his assignments and will complete them as needed for Wednesday.”

Mateo grins when I hang up. “I forgot how good you are at imitating people,” he says.

“You ain’t seen nothing yet,” I say, giving Ivy a meaningful look. The kind that says, If you don’t want this to happen, there’s still time to stop me. She doesn’t, so I redial the number, this time putting my phone on speaker so she and Mateo can hear. When the message beep sounds, I adopt a hearty baritone. “Hi, this is James Shepard. I’m afraid Ivy won’t be in school this morning— she’s feeling under the weather. Thanks, and have a great day!” Then I hang up as Ivy collapses against her car, hands on either side of her face.

“I can’t believe you did that. I thought you were bluffing,” she says.

“You did not,” I scoff.

Her answering half smile tells me I’m right, but she still looks nervous. “I don’t know if this is such a good idea,” she says, digging the toe of her loafer into the ground. Ivy still has the prepster look down cold, but she’s moved into darker colors with her black sweater, gray plaid miniskirt, and black tights. She looks better than she did in middle school when she was all about the primary colors. “We could probably pass it off as a prank—”

“What about me?” Mateo interrupts. We both turn to look at him as he inclines his head toward me, eyebrows raised. “You good enough to imitate my mom, Cal?”

“Not since puberty.” I dial Carlton High’s number one more time, then hold out my phone to Ivy.

She takes a step back, eyes wide. “What? No. I can’t.” “Well, I can’t,” I say as the recorded voice starts its spiel up once again. Nobody would believe Mateo’s dad calling in for him. That guy has never been involved in anything school- related. “And neither can Mateo. It’s you or nothing.”

Ivy darts a glance toward Mateo. “You want me to?”

“Why not?” He shrugs. “I could use a day off.”

My phone beeps as the voicemail kicks in, and Ivy grabs it. “Yes, hello,” she says breathlessly. “This is Elena Wo—um, Reyes.” Mateo rolls his eyes at the near slip on last names. “Calling about my son. Mateo Wojcik. He’s sick. He has . . . strep.”

“Ivy, no,” I hiss. “I think you need a doctor’s note to come back from strep.”

Her shoulders get rigid. “I mean, not strep. A sore throat. I’m getting him tested for strep, but it probably isn’t strep. It’s just a precaution. I’ll call back if he tests positive, but I’m sure he won’t, so don’t expect to hear from me again. Anyway, Mateo won’t be in today, so bye.” She hangs up and practically throws the phone at me.

I shoot Mateo a frozen look of horror, because that was a disaster. Whoever listens to it might actually check in with his mom, which I’m sure is the last thing he needs. I’m expecting him to shift into turbo-annoyed mode, but he starts laughing instead. And all of a sudden he’s transformed—Mateo cracking up looks less like the guy who brushes past me in the hallway as if he doesn’t see me, and more like my old friend.

“I should’ve remembered you can’t lie to save your life,” he says to Ivy, still laughing. “That sucked.”

She bites her lip. “I could call back and tell them you’re feeling better.”

“Pretty sure that would only make things worse,” Mateo says. “Anyway, I meant what I said. I could use a day off.” The parking lot has emptied out, and a bell clangs loudly from inside Carlton High. If we’re going to back out, now would be the time. But even though none of us says anything else, nobody moves, either.

“Where would we even go, though?” Ivy finally asks when the second bell rings.

I grin. “Boston, obviously,” I say, pressing the key fob to unlock my car. “I’ll drive.”