What if we saw our bodies as part of our heritage? A connection to our ancestors that we can explore, challenge, and maybe even celebrate?

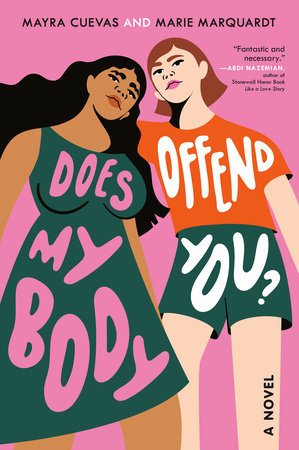

Does My Body Offend You? authors Mayra Cuevas and Marie Marquardt ask these questions and dive into our relationships with our bodies in this piece for Underlined.

Our Bodies, Our Stories

by Mayra Cuevas and Marie Marquardt

Bodies.

Our world pays so much attention to them. In just one day, our social media feeds send dozens of messages about how to dress them, tighten them, squeeze them, reduce them, make them more limber, make them stronger or bigger or smaller, reveal parts of them, or hide the “unwanted,” the “ugly” bits.

But what if we reframed the conversation? What if instead we saw our bodies as part of our heritage? A connection to our ancestors that we can explore, challenge, and maybe even celebrate?

Our bodies are an important part of our individual identity, but they’re also so much more. They take not only their physical shape but also their meaning from our cultures, which are connected to the land, our families, and our communities.

In our experience, all of this can be . . . well, complicated.

Mayra, an Island girl who comes from the land

My body comes from an ancestral lineage of Taíno people, the native inhabitants of Puerto Rico; enslaved Africans; and Spanish conquistadores. And if my late abuelo Arsenio was right, some French from the island of Corsica.

Of all the family photos hanging at home, my favorite is a portrait of my abuela Cuqui taken sometime in the fifties. In the photo, she is in her twenties and staring fiercely at the camera. There’s a beautiful intensity behind her dark eyes and in her refusal to smile. Her short brown hair is styled in soft curls and her full lips are painted in a dark shade of—dare I say, red? The photo is black and white, so I will never know. But one thing is clear: the muscles on her arms are powerful—the arms of a farmer.

For more than four decades my grandmother was an unknown trailblazer—a woman farmer who took on the work of a man, digging into the dirt with her bare hands, growing lettuce to make a living for her family and send three new generations into the world. My body comes from her body. A body that gave life in different ways—it birthed two children, one of them my mother, and it nourished countless others through the food she cultivated.

When I look at that photo, I see my dark eyes, the same soft curls framing my face, and my full lips that I love painting red. When I look at that photo, I see only strength reflected back at me. Strength from a woman who survived a lifetime of grueling work and an alcoholic husband, a woman oppressed by a culture of machismo and toxic masculinity. I see the strength of a woman who had to make sacrifices and stand up for herself. A woman who speaks her mind, doesn’t mince words, and calls it like she sees it.

Today, at eighty-seven years old, standing five feet tall, my abuela Cuqui is still a force. And although I don’t get to see her as much as we both would like, she is with me every day. I pass her photo on the way to the kitchen, and on days when the world is unkind, her proud stance reminds me of where I come from: a long line of strong women who have survived all manner of misfortunes, historical atrocities, and even cataclysmic forces of nature. Her stance reminds me that I am not alone. Her strength is my strength.

Marie, a daughter and a mother to bold women

My body comes from a complex lineage. I was built from French, German, Irish, Welsh, and English ancestors. Yet, when people look at me, most simply see a white American woman of average height and size. My ethnic history isn’t the only thing that’s obscured. The casual viewer can’t see that I grew up in a family of confident and creative women—poets, artists, and business owners who lived boldly, often defying norms and expectations.

The love of my life is an extremely tall redhead whose six-foot-eight-inch body came from his mother, a woman of formidable physical presence. My mother-in-law claims to be six-one, but we all know she’s taller. She developed the habit of fibbing about her height because her husband was six-two, and she married him in a time and a culture that radically devalued her marvelous stature—even though she was an elite tennis player.

My mother-in-law often bemoans having passed on her height to my daughters. She tells them stories of the humiliations of school dances when she towered awkwardly over the boys, and she complains about having to find size eleven shoes. My daughters, though? They love being tall. They fight over who will end up the tallest.

My tallest daughter (so far) is a six-one redhead. Last year, she asked her grandmother for a pair of platform Doc Martens as a holiday gift—size eleven, of course. Her grandmother was incredulous: She wants shoes that make her look taller? Are you sure? But she bought the shoes. And let me tell you, those shoes are badass. They’re my daughter’s favorite.

My daughter gets asked two questions almost every day: How tall are you? and What sport do you play? And every time her school gets a new basketball coach, the coach chases her through the halls for a few weeks, begging her to join the team. She will never join. My daughter doesn’t play sports. She lives for theater, and onstage she is an absolute force, a presence to behold.

Over the years, I’ve watched my daughter set aside meanings and expectations given by her own family and community, finding new ways to live into and “re-signify” the marvelous body she inherited. I’ve recognized that spark of creativity, and I’ve known that some part of her spirit comes from my own mother and grandmothers, even though she doesn’t look a thing like them.

Finding the stories that make us

Those of us who have the privilege to know our family history also have the opportunity to search for the meaning behind the parts that make our body. Sometimes we have to create new meanings for our bodies, or change our bodies so that they align with who we really are. At other times, we have the beautiful privilege of celebrating our bodies with our families and communities, honoring the ways our bodies connect us.

Our bodies carry our ancestral history, and if we look past the surface we will find the countless stories that make us. We may find disappointment, but we may also find strength, self-awareness, and deeper connections to the people whose parts we call our own.

Check out Does My Body Offend You? by Mayra Cuevas and Marie Marquardt

About the Authors

Marie Marquardt is the author of the YA novels Does My Body Offend You? with Mayra Cuevas, Dream Things True, The Radius of Us, and Flight Season. Her books have earned many awards and commendations, including being selected as BEA Buzz Books and Books All Young Georgians Should Read, as well as receiving a CLASP Américas Commendation. Marie’s novels have been shortlisted for several state book awards, including the South Carolina Young Adult Book Award and the Missouri Gateway Readers Award. Marie has also published articles and coauthored two nonfiction books about Latin American immigration to the United States, and has been interviewed about her research, writing, and advocacy on National Public Radio, Public Radio International, and BBC America, among many other media outlets. She lives in a busy household in Decatur, Georgia, with her spouse, four kids, several chickens, a dog, and a bearded dragon. You can connect with Marie on Instagram at @Marie_Marquardt and on her website, MarieMarquardt.com.

Mayra Cuevas is the author of Salty, Bitter, Sweet, a foodie romcom for young adults, named a “Best Books of Winter 2020” by Hypable, and “YA Books We Can’t Wait to Read in 2020” by BuzzFeed. Born and raised in Puerto Rico, Mayra is a professional journalist and fiction writer who prefers love stories with a happy ending. Her debut fiction short story was selected by best-selling author Becky Albertalli to appear in the Foreshadow short-story anthology. She is a co-founder of the Latinx KidLit Book Festival and member of Las Musas Books authors collective. She is currently a special projects producer and writer for CNN. She keeps her sanity by practicing Buddhism and meditation and serving on the Board of Directors of Kadampa Meditation Center Georgia. She lives in Atlanta with her husband, also a CNN journalist, their fluffy cat and a very loud Chihuahua. She is also the step-mom to two amazing young men who provide plenty of inspiration for her stories.

Did you enjoy this article from the Does My Body Offend You? authors? Get social with us at @getunderlined!