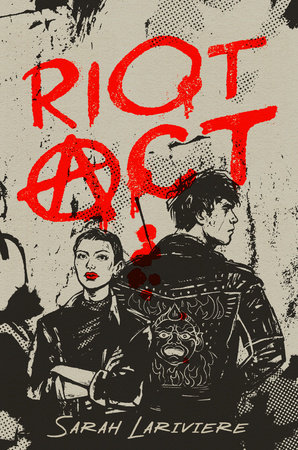

Hearing how authors turned their ideas into the books we love to read is one of our favorite parts of working in publishing! This time, we asked Sarah Lariviere, author of Riot Act, to take us behind the scenes and share what went into the making of her punk rock, alt-history story. Read on to see what she has to share about the inspiration behind the book, her writing process, and advice for aspiring writers.

Introduce yourself!

Hi, I’m Sarah Lariviere, a novelist, former clinical social worker, and tender of wild gardens in Los Angeles, California.

What was your inspiration for Riot Act?

I wrote Riot Act because I’m inspired by kids around the world who fight for freedom of expression, and haunted by the ghosts of those who die for it. The details of the story emerged from a rather personal constellation of influences. Studying abroad in Budapest, Hungary, in the mid-1990s, when I was fascinated with artists who made daring work under censorship; growing up in a sea of cornfields under the huge, omniscient-seeming sky of Champaign, Illinois; the intimate bonds I forged as a teenager when I stumbled into the world of theater.

Why did you choose to set the book in 1991?

Setting the book in 1991 was an instinctive choice, an experiment that went right. I was in high school in 1991, and, like the characters in Riot Act, I was a passionate, artistic teen who despised authority. Drawing upon my own experiences during that historical period in that particular setting allowed me to connect deeply to the stakes—to try to answer for myself the question, Would I have been willing to die for art? If so, under what circumstances? That epoch was also the dawn of the internet, when the first universally accessible browser was being developed at the University of Illinois supercomputing lab. This seemed like interesting territory to explore in the context of the book, which supposes that a dictatorship took hold of the country in 1988.

How would you describe your writing process for this book?

For maybe a year or two, I was toying with this amorphous concept, an alt-history YA series about teens fighting authoritarians in Champaign in ’91. When I finally sat down with a blank page to start writing, the narrator, Maximus Bowl, started talking immediately, as if he’d been waiting for me since he died. It was shocking and overwhelming and wildly entertaining, trying to keep up with him, and understand his story. He’s a talker, very explicit, and we share a sick sense of humor. Max was willing to go absolutely anywhere, and I fell in love with him.

But figuring out the logistics of the tale took some time. Determining the sequence of events, and the most suspenseful path to carve through this very specific, very dark world. Happily, my acquiring editor, Kelly Delaney, had the utmost faith in the project, and gave big notes early, showing warmth and confidence in me—as is her way! Then, when Kelly moved to Crown, Erin Clarke, another editorial genius, inherited the manuscript. Erin helped me home in on the heartbeat of the tale and consider the relevance of the many crazy tangents that were seducing me. Both editors fundamentally got what I was trying to do, and helped me take a bombastic, expansive story and make it razor-sharp.

I should also mention research. Before, during, and after writing the early drafts, I read maybe a million books about surviving authoritarian regimes, the birth of the internet, Greek theater, anarchy, and nonviolent protest. Reading the newspaper every day was a grim reminder of the story’s contemporary relevance. I saved way more articles than I’d like there to be about censorship in the U.S. and around the world. I mean, I want the articles, I just wish they didn’t have to exist.

Is there a behind-the-scenes anecdote about writing Riot Act that you’d like to share?

In the novel, I gave the main character, Gigi, all my beloved stuff: the car I drove in ’91, a brown 1979 Chevrolet Malibu Classic I bought for six-hundred bucks; the navy jacket with my last name stenciled on the pocket; a job hostessing at the Round Barn Restaurant. When I worked at the Round Barn, there was a six-CD changer that only ever played one CD, “Billboard Top Hits 1976.” I didn’t include this detail in the book, but every single song on that CD haunts me. Hearing “Dream Weaver” by Gary Wright or “Fooled Around and Fell in Love” by Elvin Bishop at Target will send me into an absolute fugue state. I can’t tell if it’s bliss or trauma or what—but the music on that CD is lodged in my amygdala and has a destabilizing effect on my bones.

Do you have a favorite scene from Riot Act? (No spoilers!)

Oh yeah. One of my favorite scenes is the raging dance party at the boarded-up theater where Axl squats. It was difficult to write—evoking the mood of danger and ecstasy, trying to convey the perfection of the Digital Underground song “The Humpty Dance,” while exploring some complex disappointment about sexual intimacy. This challenge made me happy.

What message do you hope young adult readers take away from reading Riot Act?

My intention is for readers to ask themselves the same question I asked myself, the one that inspires this story: Would I risk my life for freedom of expression? And a subsidiary question: Is violence justifiable when fighting a totalitarian government? In Riot Act, I needed to lay out all of the arguments for and against the importance of art, for and against violent revolution. All I want is for readers to take these questions seriously. To honestly reflect on how they make them feel.

Do you have any advice for aspiring writers?

Most writers probably give the advice that they themselves need to hear, so take this with a grain of salt. But from my position “on the other side” of the published vs. unpublished divide, I’ll offer, finish your book. Get feedback, revise it. Write another one. You can become a better writer, for sure. In my experience, part of the process—maybe the most difficult part, after actually writing a book—is learning to tolerate cold rejections; comments that feel wrong, mean, or confusing; and continuously recognizing your own ugliness, on the page—the cringiness of your early drafts, the feeling that a beautiful shining book is infinite amounts of work away. It might be. Infinite amounts of work. But if you have the vision, and put in the work, the magnitude of what’s possible is really astounding. In my experience, the more you work, the more secrets the book reveals about how to write it. And work isn’t always writing. Sometimes, it’s silent reflection, or meditation. Learning how to manage suffering, despair, and hopelessness is crucial, I believe, to becoming a clearer, more vibrant, and ultimately more successful writer.

If you could describe Riot Act in one word, what would it be?

Explosive.