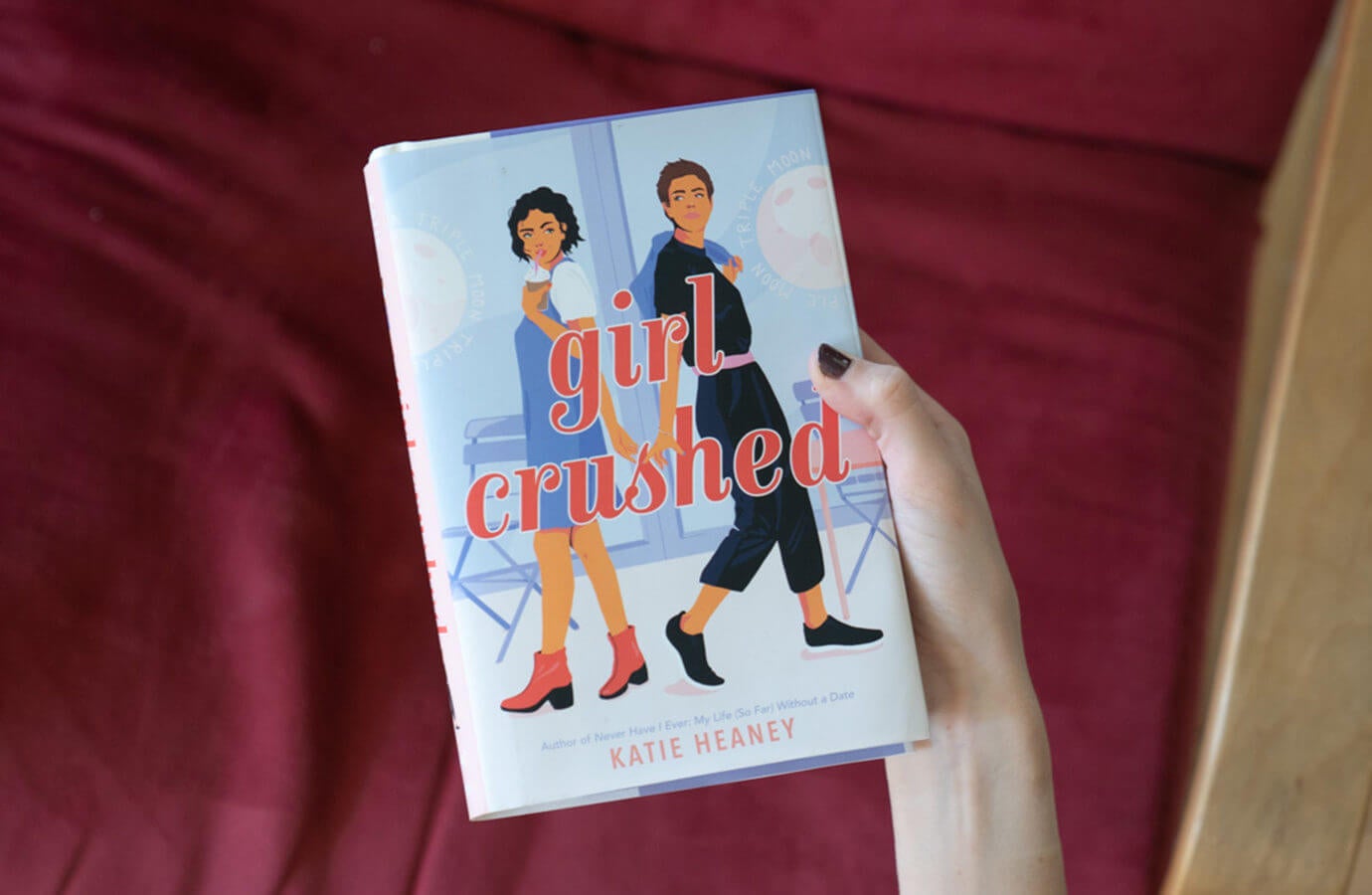

Girl Crushed by Katie Heaney is a pitch-perfect queer romance about falling in love and never quite falling out of it—heartbreak, unexpected new crushes, and all. Start reading now…

The way I saw it, I had two options.

One: I could walk into school acting how I felt—i.e., sewage seeping out of a gutter.

Two: I could walk into school acting how I wanted Jamie to think I felt—i.e., happily single, carefree, and one hundred percent over her.

I could pretend it no longer bothered me that she’d dumped me a month before we started our senior year, thus destroying all the elaborate—forgive me—promposals I’d already started thinking up, and the love letter I’d started drafting for her year- book. Never mind how many hours I’d wasted mapping the perfect road trip course between NYU (where she’d be next fall) and the University of North Carolina (where I’d be), the perfect plan to keep us together even in the face of medium- long distance. Jamie would never have to know I’d begun the initial research on a surprise fall-break trip to Washington, DC, the natural halfway point between our colleges, because Jamie talked about it like it was Disneyland. She wanted to be the third woman president—third, specifically, because it would be pathetic and disgusting if there weren’t at least two other women presidents before she was old enough to run herself. Her words.

I looked at the dashboard and realized I’d been gripping the wheel of my parked truck in the student lot for eleven full minutes. And I was still too early. For the first time since I’d gotten my driver’s license, Jamie hadn’t ridden with me to school. After she dumped me, she texted me to say she thought it would be best if she caught a ride with Alexis for a while instead. I hadn’t thought that far ahead yet, hadn’t imag- ined all the things we did together that I’d have to start doing without her. It made me wonder how long she’d been thinking about breaking up with me before she did it.

Fine with me, I’d texted back. You’re pretty out of the way.

(Obviously, that was before I’d decided to be cool and ma- ture and happy, honestly, about this whole thing.)

The upside to driving to school alone was that I could listen to any kind of music I wanted, and no one could complain, or ask me to play some horrible new indie band’s EP instead. The downside was that, so far, I’d used my newfound freedom to blast my Tragic Lesbian Breakup playlist sixty-four times in a row. A sampling: “One More Hour” by Sleater-Kinney, “Where Does the Good Go?” by Tegan and Sara, “Cliff’s Edge” by Hay- ley Kiyoko, “Give Me One Reason” by Tracy Chapman, “My Heart Will Go On” by Céline Dion. Maybe Céline Dion wasn’t gay (allegedly), but whatever. The song broke my heart in ex- actly the way I wanted my heart to be broken.

I thought about giving it one last listen before I left the truck, but I didn’t want to be the girl caught cry-mouthing whereverrrrr you aaaaahhhhh in the parking lot at 7:32 in the morning on the first day of school. Instead I closed my eyes and repeated in my head: I am happy. I am carefree. I am totally over Jamie. We were just going to be friends now, and some- day, if not today, I would be completely cool with that, because I had promised her I could be. Of course, being friends was her idea. This was part of her very practical reason for break- ing up with me. Jamie had told me that romantic relationships always ended, and most of them ended badly, and if eventually we were going to break up (and we would), we might as well do it early. Damage control, she called it. This way, she said, we could more likely stay in each other’s lives indefinitely. As friends.

Imagine being told the reason your girlfriend can’t date you anymore is that she likes you too much. It’s very confus- ing. I asked and I asked but she could never explain it in a way I understood. So eventually I had to stop asking.

And of course, a part of me had wanted to refuse, to tell her through tears that I don’t know how to be just friends with you anymore, because maybe if I could borrow a line from a TV show it would feel like a TV show instead of my actual life. After she’d left my house I’d paced around the living room, working up the nerve to call her and tell her. But every time I tried to imagine not talking to her, I couldn’t. It was like my brain didn’t have the right files. Does not compute. And any- way, it didn’t really feel like a choice. If I admitted I couldn’t be friends with her, I lost, even more than I already had. I’d have to be the one to sit somewhere else at lunch. I’d be the one who had to stay home when Jamie and our other friends hung out. I’d lost my girlfriend, and that was already more than I could take.

So we would be friends, and it would be fine. One day I wouldn’t dread walking into the class I knew we had together—a now-unwanted miracle, really, since Jamie was always in AP everything and I was not. One day I’d be able to sit down to lunch with her and Ronni and Alexis without worrying exactly where I sat, because the spot next to her wasn’t safe, and neither was the one directly across from her. One day I’d again be happy instead of furious that our lockers, thanks to the goddamn alphabet, were separated only by the locker assigned to Alex Ruiz, who, historically, didn’t seem to make much use of it. He was popular, and the popular boys never seemed to carry books or folders or anything, really, around school with them. It was like they were here for some- thing else altogether. I once asked my straight friends (Ronni and Alexis) to look into this issue for me, but they shrugged it off. Alexis said, “Who knows why they do anything the way they do?” They being boys, in general.

At home, and in the safety of my truck, I still ached when I thought about that last conversation with Jamie. I still held back tears multiple times a day. But I knew I couldn’t be that version of me in school if I wanted to make it through the year. It was bad enough knowing in my bones that everyone at school had already heard that the only out queer couple in Westville’s incoming senior class had broken up, and worse, that I was the dumpee—Alexis had surely been briefed by Jamie, which meant it was only a matter of time until people three school districts away found out. If I started my senior year as the tragic spinster lesbian, that would be how every- one remembered me. At our ten-year reunion, instead of ask- ing me what it was like playing for the U.S. women’s national soccer team, or how many free shoes I got as a result of my Adidas sponsorship, or if they could go for a ride in my Aston Martin, my former classmates would ask me if I still kept in touch with Jamie (who would be too busy in the Senate to attend), and from their expressions I would know they were really asking if I’d ever gotten over her.

I couldn’t let that happen. Everything I felt had to stay here, in the truck, with Céline. I slung my backpack and soccer bag over my shoulders, and by the time I’d crossed the parking lot I really did feel like a new person, almost.

***

I thought I saw Jamie about a dozen times before I actually did. In the hallways, between classes, I kept seeing girls with dark hair, and my throat would go hot with panic. Then I’d get another look and realize they didn’t look like Jamie at all. It was embarrassing, and draining, and by lunch I was almost eager to see her, just to get it over with. Our first post-breakup encounter had to happen sometime; this way, at least, I was prepared for it.

I spotted Ronni sitting at our usual table, alone so far and completely unembarrassed by it. Even though I’d seen her last weekend, at the last club tournament of the year, I rushed toward her like it had been months. When Ronni saw me, she cupped a hand around her mouth and yelled “RYAN!” at the same time as I yelled “DAVIS!”

Ronni Davis was my first real best friend, long before I ever met Jamie. We met in sixth grade, when I finally made the Surf Club’s premier soccer team after spending two years stuck on the Triple-A team. Ronni had made the premier team from the start, way back in fourth grade, and when I moved up, she was the only girl who said hi to me on the first day of practice. Everyone else ignored me, laughing too loud at their dumb, private middle-school jokes, throwing me and my floppy boy’s bowl cut the occasional skeptical glare. After a week or two I was one of them, having proved I was good enough to be there, but at the time, it felt like earning their approval took years. If it hadn’t been for Ronni, I might have quit, or begged to be put back on my old team, where at least I was the very best player on the medium-good team. We were inseparable, until I met Jamie. Jamie eclipsed everyone and everything, for me.

Oh God, I thought. Keep it together, Ryan.

As I reached our lunch table, I dipped into a subservient bow before Ronni. “My liege.”

Ronni shook her head. “You are so corny.”

At the end of our junior year, Ronni had been elected cap- tain of our high school team over me, and I was devastated. I’d expected her to be chosen as club captain, which she also was, but I’d hoped somehow that I could be captain at school. Being captain didn’t mean much of anything as far as college recruiters cared, but I wanted it anyway. I had never been the head of anything. I wanted the word captain printed below my name in the yearbook as a matter of public record: I meant something.

Now all my short-term hopes and dreams rested on being named the United Soccer Coaches National Player of the Year, or Gatorade Player of the Year, like Ashlyn Harris, UNC alum and butch style icon, who earned both when she was in high school.

In the end, of course, I wanted to be Megan Rapinoe: World Cup champion, Golden Boot and Golden Ball winner, the best and most beloved player in the world. I wanted my name on jerseys and my face on girls’ walls. There was still time.

In any case, I got over the lost election after a week or so. For one thing, it quickly became obvious that Ronni would be a better captain than I ever could have been. Unlike me, she wasn’t afraid of our coach, even though Coach was ob- jectively terrifying. At our last few school-season games as juniors, when she was captain-elect if not yet captain in practice, she stood next to Coach on the sidelines on the rare occasion she wasn’t playing, and together they assessed the rest of us with their arms crossed. Ronni looked so grown-up and official, exactly in the right place. Besides, the captain couldn’t be everyone’s best friend, just like a boss could never be real friends with her employees. Free of the responsibility to critique my teammates when they messed up a play, I could instead be the one who cheered them up after.

I unwrapped my sandwich and took a bite, hoping food would soothe the anxiety humming in my chest. Now that I was sitting down, I felt trapped—and paranoid. I couldn’t keep my eyes off the cafeteria doors. Ronni smacked a hand on the table.

“I thought we agreed: no liverwurst!”

“It’s the first day of school!” I protested. “It’s a special oc- casion!”

Ronni made a face. “Fine, but I don’t want to smell that smell again before your birthday.”

“What about your birthday?” I countered, and it was at that moment that I saw Jamie out of the corner of my eye. She’d just walked in with Alexis. I swallowed fast, too fast, and tried to obscure my small coughing fit in the crook of my elbow.

“You okay?” said Jamie.

How dare you, I thought. Ronni clapped me on the back, which only made me cough more. So far, this was going ex- tremely well.

“Do you need the Heimlich? I’m still certified from my Red Cross babysitter training . . . ,” offered Alexis.

“Someone who actually needs the Heimlich isn’t gonna be like, ‘Yes, thanks, that would be great,’ ” said Jamie.

“I’m fine,” I rasped.

“You sure?” asked Jamie.

It was clear from the way she asked that Jamie wasn’t

just wondering whether or not I was done choking in front of her. Maybe she was trying to be nice, but as far as I was concerned, she could pluck those pity eyes right out of her head. I couldn’t make her un-break up with me, but I could certainly deny her the pleasure of knowing how much it still hurt. I could be friendly, but she couldn’t rush me right into unloaded friendship, either. I nodded quickly and changed the subject.

“Alexis,” I said, “give us the goods. What have you heard so far?”

Alexis was our school’s own Us Weekly. If anyone in our class hooked up with anyone, or got in a fight with anyone, or got detention, or got wasted over the weekend, Alexis knew about it, and she would relay the episode to us in more de- tail than anyone needed, and often more than anyone wanted. She had sources in every social group. People told her things because she had a small mouth and huge, understanding blue eyes, but also because she told them things in return. People only pretended to care when their secrets got out. We all knew that to get the best gossip you also had to give it. And there was no day better for the very best gossip than the first day back after summer break.

“Well,” said Alexis, eyes gleaming. She leaned over the table conspiratorially, and I breathed in relief. For as long as Alexis talked, I would be safe: I wouldn’t have to look at Jamie, or think of what to say to her, or notice Ronni and Alexis watching us interact, trying to judge whether or not we were “okay” yet. What would that look like, anyway? We weren’t to- gether anymore, but we were both here. I wasn’t yelling and I wasn’t crying. If they expected more from me than that, I’d go sit somewhere else. No—they could sit somewhere else. No, wait—that would leave just me and Jamie. Ugh.

“—and, Ruby and Mikey broke up,” Alexis was saying. “A few weeks ago, apparently.”

“Wait,” I said. “What?” Jamie and I made eye contact for only an instant, but it was long enough to know we’d both had the same exact thought: Ruby Ocampo, number one on the list of Straight Girls We Wish Weren’t. I hadn’t thought about that list in a year.

Alexis misinterpreted my confusion as shock and clapped her hands in delight. “I know!”

“What about Sweets?” Jamie asked.

“Who broke up with who?” I asked.

Sweets was the name of a band composed of four Westville

seniors: Mikey Vingiano on bass, Ben Cooper on drums, David Tovar on guitar, and Ruby Ocampo on vocals. Like many of our classmates, Jamie was obsessed with them. She’d sent me links to their SoundCloud page about a dozen times before I actually clicked on one, and even then I only lasted about twenty seconds. Ruby had a nice voice, but calling the noise underneath it a “song” felt generous. Jamie had told me I had to see them live to get it, but I often had soccer games when they had shows, and the rest of the time I invented menstrual cramps. They played most of their shows at the Six-Pack, which was the idiotic name given to the dilapidated old house in which Mikey’s older brother lived with three other college sophomores. Jamie said it wasn’t so bad, but when I pictured it I saw a dark and sweaty basement overflowing with smelly boys nodding to the music and drinking flat beer. I’d asked her if that sounded right and she agreed: it was more or less just like that. So, no thank you.

“Ruby broke up with Mikey,” said Alexis. “And Sweets is fine, for now . . . but apparently Mikey revoked use of his brother’s house as, like, punishment for the breakup, I guess. So they need a new venue.”

“What a little bitch,” said Ronni. We didn’t have to ask—we knew she meant Mikey.

“I wonder if they could play at Triple Moon,” said Jamie.

“Ha!” I laughed. “Right. I’m sure those guys would love to play at a lesbian coffee shop.”

“Why not?!” Alexis nearly shouted. Alexis was very of- fended on Jamie’s and my behalf whenever someone did or said something vaguely homophobic. Because Jamie was Jew- ish and Ronni was black, Alexis also took anti-Semitism and racism very personally. Needless to say, she found most things sexist. Her backpack was covered in pins that read straight but not narrow and coexist and who run the world? girls and black lives matter, the last of which Ronni gave her to replace one that read one race: human.

“They need somewhere to play, don’t they? And Triple Moon has shows,” said Jamie.

“Yeah, like . . . spoken-word shows.”

“I dunno,” said Jamie. “I think Dee and Gaby would be down. A lot of people like Sweets. It’d be good for business.”

“I’m sure they’d be fine with it. I just think those guys would sooner play a Panera Bread than Triple Moon.”

“Maybe a break will be good for them,” said Ronni. “You know, take some lessons . . . learn to read music . . .” (Fine: I’d sent Ronni the link I’d listened to.)

I cracked up. Jamie looked annoyed. “They know how to play. You guys just don’t get it.”

“You got me there.” Ronni shrugged.

“I get it,” I argued. Suddenly I was mad. “I just don’t like it.” “The one song you listened to?”

“One was enough.”

My heart hammered against my ribs, and I saw Ronni and

Alexis exchange a quick look, just like I knew they would. We were making them uncomfortable, which was the last thing I wanted. No matter how stupid Jamie had made me feel, I had to be cordial. I didn’t want to give them the opportunity to pick sides unless I knew for sure they’d take mine.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “Triple Moon isn’t a bad idea.”

Jamie stared at me for a moment. It took everything I had not to look away before she muttered, “Thanks.”

Under the table Ronni grabbed my wrist and squeezed it. I couldn’t look at her or I’d cry, so instead I slid an Oreo into my mouth and focused on chewing that instead.

The good thing about not having Civil Liberties until last pe- riod was that I got a break from seeing Jamie for two hours. The bad thing about having Civil Liberties last period was that I spent those two hours dreading seeing Jamie. She shouldn’t have even been in Civil Liberties, which was, for most people, a civics graduation requirement taken at the last possible sec- ond. Jamie, however, had already taken AP Government junior year, and was taking Civil Liberties for “fun,” which to me felt a little like a billionaire choosing to take the bus.

At passing time I stepped into a stall in the girls’ bathroom and waited the remaining four minutes out, not wanting to get there before she did. When the warning bell rang I checked my teeth in the mirror and pulled and poked at pieces of my hair until it looked almost normal, and then I walked into class. And for a moment—just a moment—I considered walking right back out.

There was only one open seat left: the one closest to Mr. Haggerty’s desk. Sitting in the seat directly behind that one was Jamie.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” I muttered to myself.

I dropped my bag alongside the desk, and Jamie gave me a bashful, closed-mouth smile.

For the first time in my life, I prayed to be given a seating chart. And I prayed it would put me as far away from Jamie Rudawski as possible.

Mr. Haggerty introduced himself and took roll call, paus- ing to make notes when someone corrected his pronunciation or specified a nickname. We could have done the whole rou- tine collectively, on each other’s behalf, so many times had we heard each other’s names read aloud over the last three years.

I stared at the surface of my desk, imagining I felt Jamie’s eyes boring into my brain. Don’t let her catch you thinking about her, I thought. Ah, I mean—shit.

Then Mr. Haggerty called out, “Ruby Ocampo,” and I looked up.